The Swastika Symbol: An Integral Part of Raton’s Past

By Pat Veltri

THE SWASTIKA: GENERAL INFORMATION

Stalwartly unfurling around the crown of the tallest building in Raton, embellishing the outer brick surface, is the swastika motif, a reminder of a bygone era from the heyday of the ritzy Hotel Swastika. Nowadays, the building houses the INBank, but not for much longer, as the building was recently sold to Andrew Leafe, who plans to “revitalize and bring back the hotel”, according to an article on the KRTN Radio website.

Just a few blocks north of the former hotel stands the venerable Shuler Theater. More than a century old the building is a significant venue for professional theatrical performances and concerts, as well as amateur productions. The building is also used for the hosting of radio station KRTN’s This, That and The Other program. One of the theater’s original drop curtains, still in use, features a scene from the Cimarron Palisades surrounded by a border of Native American patterns, including swastika symbols painted on the curtain’s folds.

Currently unoccupied, the former Swastika Fuel Company building still stands on the northern part of Raton’s Historic First Street. The Swastika Fuel Company, a subsidiary of the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company, was engaged in the business of selling coal and coke to various outlets.

Concrete foundations, low walls and black mine dumps are scattered around the landscape of a secluded canyon a few miles west of Raton. Situated on the privately owned Vermejo Park Ranch, these leavings along with a few other recognizable vestiges of town buildings are about all that is left of the coal camp of Swastika.

These architectural forms, decorative touches and business logos, all enveloped in the swastika symbol, have had a lasting importance in the community and played an integral part in Raton’s past. Implicitly, the lasting importance of this symbol is reflected in the ninety-five year old former Hotel Swastika, an architectural gem in the Pueblo Deco style; a century old drop curtain in the Shuler Theater; the former Swastika Fuel Company headquarters; and the nostalgic ruins of a former coal camp – all acknowledging what were essential components in terms of the production and consumption of goods and services during the era of King Coal in Raton and Colfax County.

About the Swastika Symbol

The swastika is a universal good luck symbol that emerged independently among many cultures and has been commonly used for thousands of years by most indigenous peoples the world over. Reports of how many years the swastika has been in use varies according to the researcher – it could be anywhere from 6,000 to 15,000 years. Bottom line: the symbol is ancient!

Most scholars agree that the term swastika comes from the ancient Sanskrit language of India: Su meaning “well” and Asti meaning “being” (well-being), thus the association with good luck and prosperity.

Britannica defines a swastika as a “equilateral cross with arms bent at right angles, all in the same rotary direction, usually clockwise”.

Internet source Tom Metcalfe says the symbol has been known by several names, “The word ‘swastika’ – from the Sanskrit word ‘svastika,’ meaning something like ‘blessing’ or ‘good fortune’ – is how it’s best known today. But it was a ‘fylfot’ to the Anglo-Saxons, a ‘gammadion’ or tetraskelion’ to the ancient Greeks, and a ‘hakenkreuz’ (hooked cross) or ‘winkelkreuz’ (angled cross ) to Germans since the Middle Ages”.

The Swastika Maligned

Despite the swastika’s association with abundance and prosperity, it is now widely recognized as a symbol of hate, due to the heinous actions of the Nazis during World War II.

Adolf Hitler decided in 1920 that the Nazi Party had a need for its own symbol and flag. Hitler felt that what the new National Socialist German Workers’ Party lacked was an emblem or symbol “which would express what the new organization stood for and appeal to the imagination of the masses, who as Hitler reasoned, must have some striking banner to follow and to fight under”, stated the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, the late William L. Shirer. For the new flag Hitler took the colors red, white and black of the old imperial flag and added the hakenkreuz (swastika). He added new symbolism to the colors, stating in his autobiographical manifesto, Mein Kampf, “In red we see the social idea of the movement, in white the nationalist idea, in the Hakenkreuz the mission of the struggle for the victory of the Aryan man”.The Nazis always referred to their symbol as hakenkreuz.

The Nazi flag boasted a red background, with a white circle topped with a black swastika symbol. The direction of the swastika form is often questioned. The Nazis consistently used the right facing form and tilted the swastika symbol at an angle of 45 degrees, and it was invariably black. Do all other non-Nazi versions turn in the opposite direction? Generally speaking, public opinion tends to favor this view, but research, including that of archaeologist, Robert M. Chapple, negates the assumption: “But not all other (i.e. non-Nazi) swastikas turn the opposite direction”.

How did the swastika become a Nazi symbol? Feature writer Kalpana Sunder offers this explanation: “It has been suggested that Hitler’s adoption of the symbol may have had its roots in Germans finding similarity between their language and Sanskrit, and drawing a conclusion that Indians and Germans came from the same ‘pure’ Aryan ancestry and lineage. During his extensive excavations, the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann discovered, in 1871, 1,800 variations of the hooked cross on pottery fragments at the site of ancient Troy, which were similar to artifacts from German history”. Sunder quotes anthropologist Gwendolyn Leick, “This was seen (by the Nazis) as evidence for a racial continuity and proof that the inhabitants of the site had been Aryan all along”.

The Swastika Symbol: Good or Evil?

For possibly as many as 15,000 years, the swastika symbol in both left-facing and right-facing versions stood for well-being, good luck and prosperity in many cultures. The swastika symbol underwent a nightmarish transformation when it was adopted by the German Nazi Party. In many western countries the swastika is still looked upon as a symbol of intimidation, antisemitism and racial supremacy.

Nowadays despite the association with the Nazi regime, and white supremacy, readers would do well to remember that the swastika remains an important symbol among many religions and cultures. For example in Buddhism, a left-facing swastika symbolizes the auspicious footprints of the Buddha.

Good or evil? Readers will have to decide for themselves. Jonny Wilkes, a freelance writer, expresses this opinion: “The answer, although not a neat one, may be that there will always be two utterly conflicting interpretations of the swastika, both of which are part of our history, present and future: one representing the worst of humanity and the other symbolizing the best”.

The Swastika in the Southwest

The swastika was a motif widely utilized by several Native American tribes of the southwestern region. Among these tribes the icon conveyed various meanings. For instance the swastika’s meaning to the Hopi people, as stated by author B. Jane Bush, was described as a portrayal of the migration routes Hopi clans took through North and South America. Another example, cited by swastika scholar Dennis Aigner, noted that the symbol represents the legend of the whirling log. Aigner says, “In Navajo, or Dine, cultural understandings, the whirling log motif recalls the sacred number four in many ways: the four seasons, the four directions, and the four sacred mountains”.

Around the turn of the twentieth century the swastika symbol provoked quite a bit of interest, especially in the United States, where its use became widespread and fashionable. An internet source, Kim and Pat Messier’s Blog, contends that the symbol’s popularity was bolstered partially by Thomas Wilson’s 1894 report for the U.S. National Museum (present day Smithsonian Institute). His treatise, entitled The Swastika: The Earliest Known Symbol, and Its Migrations is an in-depth study demonstrating the universalism of the swastika symbol in diverse cultures of the world.

The symbol rapidly became a popular graphical icon of the Western world, representing good fortune and success. Because of its popularity, traders and dealers encouraged Native American artisans to use it on their crafts made for sale to tourists. Visitors to New Mexico, Arizona, and other Southwestern states happily purchased souvenir rugs, pottery, baskets, and jewelry embellished with the swastika.

During the tourist era, the years between 1890 and 1940, the swastika was a fad of sorts, a benevolent good luck symbol. According to graphic design writer Steven Heller, “it was enthusiastically adopted in the West as an architectural motif, on advertising and product design. Coca-Cola used it. Carlsberg used it on their beer bottles. The Boy Scouts adopted it and the Girls’ Club of America called their magazine Swastika”. During the 1920s couturiers embraced the swastika, creating stylish swastika-themed outfits for fashionable females.

Military units used it during World War I. The 45th Infantry, an all-Native American division of the United States Army, used a yellow swastika on a red background as a unit symbol until the 1930s. The 45th Infantry division wore the swastika while fighting against the Germans in World War I.

Once the swastika symbol was corrupted by the Nazi Party certain tribes, namely the Navajo, Hopi, Apache and Tohono O’odham (Papago), disallowed the use of the whirling log motif via an intertribal proclamation. The text of the proclamation, as published by the St. Joseph Missouri Gazette, read as follows: “Because the ornament which has been a symbol of friendship among our forefathers for many centuries has been desecrated recently by another nation of peoples, therefore it is resolved that henceforth from this date on and forevermore our tribes renounce the use of the emblem commonly known today as the swastika, or fylfot, on our blankets, baskets, art objects, sand paintings and clothing”. Tribal representatives signed the parchment proclamation on February 28, 1940 in Tucson, Arizona, then gathered a blanket, a basket and some hand decorated clothing, all bearing swastika symbols, into a pile, sprinkled colored sand on top and proceeded to burn the items.

THE SWASTIKA INFLUENCE IN RATON

During the so-called tourist era, from the years 1890 to 1940, the swastika symbol was at the height of its popularity, a twentieth century fad, if you will. The design was used widely in Native American crafts and as a symbol of good luck and prosperity in advertising and industrial design. Raton jumped on the bandwagon, along with many other American cities, using the motif in architectural projects, as business logos, and slogans and as decorative embellishments. The following examples show the influence of the swastika in Raton’s past:

The Shuler Theater

The driving force behind the construction of the Shuler Theater was Dr. James Jackson Shuler. Arriving in Raton in 1881, Dr. Shuler, previously a surgeon for the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, prepared to take on the all important task of becoming the town’s first doctor. Shuler had a flourishing medical practice during his tenure in Raton looking after patients in the town, and in several of the coal camps in the area.

Within ten years time Shuler had actively plunged into the local political scene. He served two terms as mayor, one from 1899 to 1902 and a second time from 1910 until his death in 1919. Ken Sandelin, in his monograph The Shuler Auditorium: A Theatrical History stated, “It was during this second term that Dr. Shuler and the other city officials undertook a number of impressive projects, including the construction of a new municipal auditorium”.

Around 1910 Mayor Shuler and his councilmen were developing a plan for a new municipal building. Sandelin stated that the “initial plan was to build a modest city hall with $25,000 that had been voted by the taxpayers for that purpose”. In the early 1900s Hugo Seaberg’s Coliseum Garden Theater had been destroyed by fire and was not rebuilt, leaving Raton without a large theater. After months of rumination, the plan was adjusted to include a municipal auditorium, as well as a fire station, extra office space and a heating system.

To design the building Mayor Shuler and his councilmen commissioned architect William Rapp of Trinidad, Colorado. Architect Rapp presented his construction drawings to the councilmen early in 1912 and they accepted his architectural plan. About the municipal auditorium Sandelin stated, “Architecturally it was to conform to the classic opera house formula, including features such as opera boxes situated in an extended proscenium arch. Its decoration, designed by decorator F. Mayer, was a rough approximation of the eighteenth century European style known as Rococo”.

Despite some political hardships, the municipal building was completed at a cost of $55,000. The brand new auditorium, which formally opened on April 27, 1915, boasted outstanding technical equipment, well-lighted dressing rooms, a fully furnished waiting room for musicians and an elevator. Probably the most important aspect of the Shuler as a working theater, according to Sandelin, is that “It was, and is, acoustically perfect, a feature which is difficult to achieve, even today”.

Adding to the scenery, as impressive finishing touches, were four drop curtains, three of which remain in use. The drops, the work of the Kansas City Scenic Company, that are still in use include: Ripley Park in Raton highlighting the old Carnegie Public Library, a Roman palace setting framed by intricate draperies, and most importantly the original fire curtain depicting a scene from the Palisades of Cimarron against a background of Native American motifs, including swastika symbols painted on the folds of the curtain. The Palisades scene was painted from a postcard image of a photograph by William A. White. The curtains are made of 4 x 25 foot canvas panels and painted with watercolors.

Early on the theater was dubbed The Rex, but In 1919, when Dr. Shuler passed away, the original name was changed to the Shuler Auditorium in honor of the illustrious doctor who had a hand in pushing its construction forward.

Now 109 years old, the Shuler Theater continues to serve as a center for the performing arts in northeastern New Mexico. Renovated in the 1960s, at the instigation of Miss Evlyn Shuler, the doctor’s daughter, the interior showcases some beautiful treasures from the earliest days, including the drop curtains, an original restored opera box, and eight 1930s WPA (Work Progress Administration) murals by artist Manville Chapman. The building is a registered Cultural Property in New Mexico.

Swastika Fuel Company

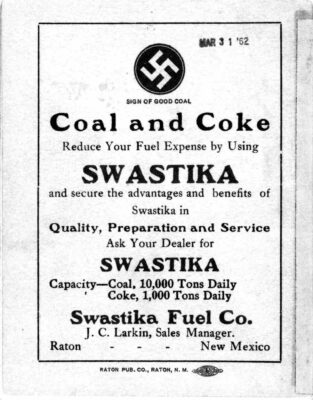

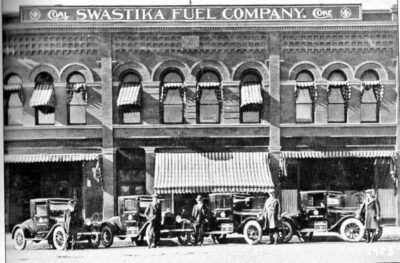

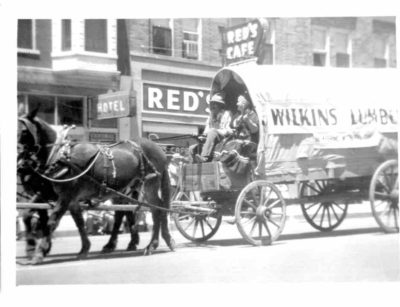

A fleet of spotless black cars, glittering in the sunlight, parked on the 100 block of Raton’s North First Street, in front of the Swastika Fuel Company, was a familiar sight during the company’s existence. The cars, marked with the symbol of swastika, were standing in readiness, along with nattily dressed drivers, part of the company’s cadre of traveling salesmen, employed to pedal coal throughout the western states. The company, taking the Swastika name, proudly advertised the symbol as a “sign of good coal”.

The Swastika Fuel Company, headquartered in Raton, was a subsidiary company established in 1908, during New Mexico’s territorial days, by the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific Company.

The incorporators were Henry Koehler Jr. (St. Louis, Missouri), Jan Van Houten (Raton, New Mexico), and Thomas B. Harlan (St. Louis, Missouri), each holding ten shares in the company. According to research conducted by Raton native Jerry Segotta, for his Master’s Degree Thesis, “An agreement was made between the Swastika Fuel Company and the St.

Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company dated February 29, 1908. Through this agreement the Swastika Fuel company received the right to purchase coal and coke from the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company”. The Swastika Fuel Company “became the outlet agent for the coal mined by the parent company”. Quite simply, Swastika Fuel Company was the selling agent for the mines of the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company.

New Mexico moved into statehood and the company continued to grow and prosper in keeping with the power of the swastika symbol. Business moved along smoothly until certain world events deemed it necessary for the company to hold a high priority meeting, called on November 7, 1938.

Segotta’s research quoted the minutes of the Swastika Fuel Company: “The president stated the advisability of changing the name of the Swastika Fuel Company to read Raton Coal Company due to the political implications in the use of the word Swastika. The necessary papers were thus filed with the state of New Mexico Corporation Commission and the Swastika Fuel company became the Raton Coal Company”.

The Raton Coal Company continued to be a prime market for the coal produced by the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company.

The Raton Coal Company pressed on with business until July 24, 1956. Due to a nationwide decrease in the demand for coal and the sale of the parent company’s mines, Raton Coal Company made the decision to “discontinue its operation”.

Swastika Coal Camp

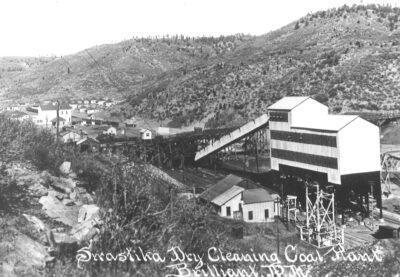

Tucked away into a remote canyon called Dillon, about six miles northwest of Raton, sits the remains of Swastika, a once flourishing coal camp that is significantly related to the early settlement and history of Raton and Colfax County. Swastika and three of its sister camps – Blossburg, Brilliant, and Gardiner – all established by the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company, are now part of media mogul Ted Turner’s extensive Vermejo Park Ranch.

Mining operations at Swastika, named for the popular Native American symbol of good fortune and prosperity, were the last to get started in Dillon Canyon. The St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company, a coal mining and coking company organized in 1905 by Henry and Hugo Koehler, initially examined the area for coal deposits in 1917, while searching for new fossil energy sources. Soon after the company had built a tipple and rail yards and set in motion the beginnings of a camp town with the construction of a boarding house and a few lodging accommodations.

The Swastika Post Office was established in 1919. By 1925 coal extraction from the mine amounted to 1500 tons per day, boosting Swastika into the position of leading producer of coal in Dillon Canyon. The success of the town’s coal production contributed to the growth of the town which by then had expanded to encompass 102 family dwellings, a school, a company store, a saloon, and a doctor’s office. Moving forward, in 1929 the town boasted a population of 500. Evidently, the good fortune triggered by the swastika was flowing for both the mining company and the miners. James E. and Barbara H. Sherman (Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico) noted, “To the local townsfolk the good fortune of Swastika meant a regular paycheck, warm comfortable company houses, education for the children, and company sponsored events and activities for their entertainment” .

Like all coal camps, Swastika’s population was a mishmash of ethnic groups, but predominately Italian. The Italian immigrants were quite enthusiastic about soccer. While competing in organized events these talented Italian athletes were almost always victorious. “When Swastika challenged opponents, generally two neighboring camps would join together to play the game against them”, stated Sherman and Sherman.

The history of Swastika began to merge with that of Brilliant, another coal camp owned by the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific Company, in the early 1920s.The two camps coexisted until Brilliant closed its post office in 1935. By then Brilliant’s coal operations had ceased to be active and it had become a “bedroom community” for Swastika. Some twelve to fourteen families lived in Brilliant, while the breadwinners worked in Swastika. The miners were chauffeured the three and a half miles to Swastika in a company truck.

By the start of World War II, the swastika motif had been maligned by the heinous acts of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime and the town was temporarily nameless. Company officials made the logical decision and renamed the camp after the discontinued town of Brilliant. Thereafter, Swastika was known as Brilliant Two or New Brilliant, or merely Brilliant.

Mining operations closed for good on July 29, 1953, and the post office was discontinued in 1954. Equipment and buildings were sold for scrap and several of the houses were moved from their foundations and transported to Raton to be used as residences.

The Hotel Swastika

When the Hotel Swastika formally opened its elegant doors on the night of June 22, 1929, some 100 couples danced to the music of the Mendelssohn Orchestra in the grand ballroom of the hostelry. Guests in attendance came from Trinidad, Denver, Las Vegas, Albuquerque, Amarillo, Dawson, Clayton, and Santa Fe. Among the VIPS present were Miss Virginia Dillon, daughter of New Mexico’s governor, R.C. Dillon, along with Lt. Gov. J.B. Anderson, and C.W. Post, superintendent of the Fred Harvey system ( a chain of hotels along the Santa Fe railroad).

An article in The Raton Reporter newspaper, dated June 7, 1929, praised the hotel as a “superstructure of brick, concrete and steel” and said that it represented a “landmark in the rapid strides of building progress in Raton”. Completely fireproof, six stories high with eighty guest rooms in addition to a lobby, lounge, ladies’ mezzanine floor, ball and banquet rooms, and a fully equipped cafe, the hotel was a marvel of achievement for the city of Raton.

A group of Raton business and professional men formed the Hotel Swastika Corporation with banker and business owner Joe DiLisio, Sr. as its president. DiLisio, Sr. was considered by some as the moving force behind the establishment of the new hotel.

Several local firms leased the downstairs areas of the hotel building. Soon after the hotel opened, a barber shop and beauty parlor moved in. George Clements and Austin Stafford were the owners. The shop, known as the Swastika Barber Shop, advertised an “expert manicurist” and a “Shine Parlor”. August Lambert’s new Swastika Drug Store was another lessee in the lower level of the hotel. Bin to User Coal Company had an office there for a while, and after prohibition was over, the space was made into a hotel bar. Peter Yob paid the Hotel Swastika Corp. $225 a month to rent space for his “modern market and grocery store” called City Market, facing on Second Street, which opened on July 29, 1929.

During his high school years in the mid 1930s,the late William (Bill) Darden, a Raton attorney, spent most of his free time working at various jobs at the Hotel Swastika. Darden, whose father Archie was a stockholder in the Hotel Swastika Corporation, was first employed at the hotel as a busboy during banquets when he was about fourteen years old. A couple of years later he worked as a bellhop and then as a room clerk.

In a 2007 interview for The Raton Range Darden described the Hotel Swastika as being “very elegant”. “It was the best hotel between Colorado Springs and Santa Fe,” he remembered. “It had a nice ballroom and a nice lounge in the main lobby. Somehow they got a bunch of Taos artists to consign some of their paintings to the hotel just for exhibition, and for sale, if people wanted to buy them, so they had a number of very nice Taos paintings in the hotel”.

Adding to the elegance, Darden explained, was the entrance to the hotel, which was fashioned “after that of the famous Blackstone Hotel of Chicago”, and included a tiled water fountain, curved stairways, and a Terrazzo floor, named after the Italian city that gave birth to the style. The lounge boasted a large fireplace of Batchelder tile – designed by California artist Ernest A. Batchelder – adorned with a single swastika symbol.

Although there were places for eighty rooms, Darden said there were only seventy-six rooms for guests: “Three of those other rooms were the manager’s apartment. He had a very nice apartment in the corner on the first floor of rooms, a three-room apartment, and then there was a room they called the linen room where the maids took care of the linens for the beds and stuff, so those four were deducted from the eighty”.

Prices of the rooms varied according to the amenities provided. The advertising brochure published for the opening of the hotel said, “Rates will be most moderate, ranging from $2.00 to $6.00 per day”.

Darden didn’t know why the hotel was given the name Swastika, but he speculated, “I presume it was named that because the name Swastika was pretty prominent around town. The St. Louis Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company was a big coal company here and its wholesale subsidiary was the Swastika Fuel Company and there was the coal camp of Swastika. Of course it was a popular name in this state because it was an Indian symbol”.

Due to the actions of Adolph Hitler, leader of Nazi Germany who had adopted the swastika in 1920, the latter part of 1938 became a crucial time in the history of the Hotel Swastika. In October 1938, Sudetenland (western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans) was put under military administration by Germany. Shortly after the annexation, Jewish people living in Sudetenland were widely persecuted by the Nazis. Hitler’s ambitious program of world domination and elimination of the Jews caused the once popular swastika symbol, widely used by New Mexico’s Native Americans in their weavings, jewelry and pottery, to become hated and feared by many Americans. “It wasn’t until Hitler took over the Sudetenland that people all over the country got stirred up about it”, Darden recalled. “Before 1937, I think the people locally thought Hitler was just swiping the swastika and we kind of laughed about it”.

Darden didn’t feel the swastika symbol was any detriment to business: “Well, I guess there were people who criticized it, but I’m sure it didn’t cause any real loss of business”.

In contrast, The Raton Reporter of November 29, 1938, painted a bleaker picture. The Reporter described how the emblem had become a liability to Raton business concerns that used it for years. The article said that the hotel had taken down the symbol from their signs and other places in the building. Hotel manager Ainslee Embree was quoted as saying, “Criticism has become so severe that it is important that the name of the hotel be changed”.

According to Embree, a sizable amount of people “made it a point to come in the hotel and announce they would not stop there as long as it portrayed the emblem”.

The hotel distributed printed cards giving the origin of the swastika showing that it had pre-dated Hitler by thousands of years, but it had little effect in swaying people’s opinions about the symbol.

In November 1938, the hotel’s board of directors voted to change its name. They announced a contest to rename the hotel and offered a prize of twenty-five dollars to the winner. The response to the contest was overwhelming. After perusing thousand of entries, the board announced on February 9, 1939, that the new name of the hotel would be the Hotel Yucca, after the New Mexico state flower. Sixteen people submitted the winning name. Hotel Ranger was the second choice, followed by Hotel Colfax as the third pick.

Hotel Swastika, and then Hotel Yucca, catered to travelers in northeastern New Mexico for forty years. By 1969, the once high-class hotel was unable to compete with the influx of motels in the area and closed its doors. In 1971, International State Bank (INBank) moved into the newly reconditioned building. Today, ninety-five years later, the building isn’t new, but its classy style is still intact. A face lift is in the making by the new owner, Andrew Leafe.

Great article. Most of us who grew up in Raton knew about the swastikas but your research provided information I was not aware of. I hope Raton and those areas of New Mexico which once honored the swastika, will keep its history alive.

This article has a really interesting discussion of the history of Raton, and some of its historic buildings. The stories of our historic buildings and their occupants paints a vivid picture of what Raton used to look like, and I truly appreciate that. However, the overall tone of this article doesn’t put enough weight behind the true HORROR of World War II and the Nazi Regime. There is not a person alive today that sees the swastika and thinks of anything other than the Nazi Regime at first glance. Regardless of the world-wide use of the symbol prior to WWII, the meaning of the symbol has been *permanently* tarnished. The swastikas in this town are not “a reminder of a bygone era from the ritzy Hotel Swastika” as described in this article. It’s a symbol of racism, anti-Semitism, and fascism. It represents one of the ugliest, most shameful moments in our world’s history. Even cultures that historically used the symbol with positive connotations distanced themselves from the symbol after the abominable events of WWII.

The history of Raton should be celebrated, but we also need to recognize that actions and symbols from the past carry a certain weight that is no longer acceptable in today’s world. The history of the InBank building and the coal camps in this area need to be addressed with a nuance and context that this article doesn’t carry. Any persistence of the swastika symbol should solely serve as a reminder to prevent anything like WWII from ever happening again. We should not celebrate that our buildings carry a symbol of hatred and genocide. We can celebrate our town’s history without celebrating a hate symbol. The swastika carries the weight of the worst of humanity, and I truly don’t want that to be the symbol anyone associates with the town I love so dearly.