Ruth Brown Saunders: Colfax County Educator

By Pat Veltri

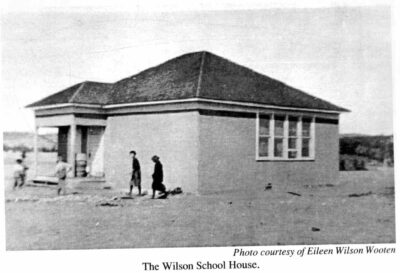

Wilson School, the First Year

Wilson School, courtesy of Bill Littrell’s book, Forgotten Schools of Colfax County, New Mexico, page 174

Depression era winters on the prairie land surrounding the tiny village of Maxwell were typically brutal. On one memorable winter day in 1930 a terrifying, fast moving blizzard, accompanied by high winds, rapidly covered the countryside with a milky white blanket of snow. A ghostly groaning traversed the enormous stretch of flat grassland as the wind whipped and howled. Blowing snow crystals gyrating in the air and near the ground assaulted Ruth Brown’s face, decreasing visibility, as she and her mare Soapstick pushed their way from Aunt Sadie’s ranch towards Wilson School. Ruth wasn’t sure the covered wagon “bus” carrying her students would make it to the school on this blizzardy day but she was determined to be ready and waiting just in case.

Wearing metal horseshoes, Soapstick didn’t have much grip on the snow and was forced to slow down to a walk. Snow built up on the underside of the horse’s hooves causing her to plow through the deep snow in a rocking motion. Ruth, barely into her teaching career, prayed fervently that her “bus driver” did not deliver the kiddos to school in this miserable winter storm. She had tried to stress to him the importance of not coming to school on bad days, but many times he would come, regardless of hazardous weather conditions, because the children would rather be in school, where they had the opportunity to be with their schoolmates, learning and playing.

Soapstick was covered with sleet and snow, and Ruth’s face was numb with cold as horse and rider finally approached their destination. Ruth quickly dismounted, noticing that Soapstick was beginning to tremble. Ruth was frantic with worry; she knew the horse should be sheltered. On impulse, Ruth took Soapstick up four steps to a small porch leading into the building and led the horse inside. She quickly built a fire in the potbellied stove. Warmth spread throughout the schoolroom as Ruth made quick work of sweeping the ice and snow off her horse.

Ruth lingered in her classroom for a couple of hours, allowing for the possibility that the bus driver might manage to transport his passengers safely to school, but he did not make an appearance. Ruth thought to herself, “The bus driver was wiser than me!” As blizzard conditions subsided Ruth and Soapstick headed in a homeward direction.

Back home, while Soapstick contentedly snacked on hay in her barn stall, Ruth held Aunt Sadie’s attention in the ranch’s cozy kitchen, with an account of her “snow day”. Aunt Sadie listened with irritated concern. She was in a fluster, but patiently explained to Ruth how bringing a 1600 pound horse inside of a building with a wooden floor had the potential for disaster! What could have happened? There was a chance that the floor might have collapsed under Soapstick’s weight, and above all there was a real danger that the horse might have been injured. At the very least the stone foundation of the school building would have had to be dismantled to rescue her. Casting her eyes heavenward in relief, Ruth silently offered thanks for the divine intervention that had prevented a troublesome situation from happening!

The above vignette was part of a 1992 interview with Ruth Brown Saunders, by a couple of members of Raton’s American Association of University Women’s group, as she shared her recollections of teaching in a one-room school. The interview, on file in the historical archives of Arthur Johnson Memorial Library, offers the reader a simple straightforward view of what teaching and learning was like in 1930, at Wilson School, east of Maxwell, New Mexico, as fledgling teacher Ruth embarked on her educational career.

During her teaching term at the Wilson School, Ruth lived with her aunt Sadie Smyth on a ranch in the Maxwell area, situated about four miles from the school. Ruth’s “Auntie Sadie”, a strong, independent widow, was managing and running the large ranch single-handedly.

There was a road leading from the ranch to the school, but it was virtually unusable for a car so Ruth spent quite a bit of time in the saddle, as her horse became her one and only mode of transport.

The school’s “bus” was unconventional and out of the ordinary, especially for the 1930s. It was literally a covered wagon, pulled by two horses, similar in appearance to a nineteenth century prairie schooner, that delivered the dozen or so students from surrounding ranches to the school on a daily basis. Straw was scattered in the bed of the wagon for warmth in the winter, and during warmer weather, the canvas sides could be lifted to let in a fresh breeze.

Wilson School was a frame building with a stone foundation, approximately 700 square feet in width and length, close to the size of a single classroom in a modern school building.

There is no discernible record of how the school came to be called Wilson, and Ruth’s interview did not make reference to the origin of the name. Possibly the only remaining documentation of one-room schools in northeastern New Mexico is Bill Littrell’s book Forgotten Schools of Colfax County. Littrell stated in his book, “Oftentimes a rancher or landowner owned the schoolhouse and other buildings or facilities that went with it. The county furnished and paid for the teacher. One of the requirements for funding was there had to be eight students.” Littrell noted that Wilson was built “as a new school in 1922” and was located “about one mile east of Tom Wilson’s headquarters and a mile north of the Fudge Ranch headquarters.” Aside from that, over a period of years, several students with the surname Wilson were listed on the school’s roll. It’s a fair bet that the school name came from Tom Wilson or another member of his prominent ranching family, probably as a landowner but maybe as a donor of school property.

Students in the Wilson School had to make do without electricity or indoor plumbing. A humble, but utilitarian outhouse sat starkly on the prairie, about 150 feet from the school building. Ruth recalled that the wind was so ferocious at times that she often had to send an older child to accompany one of the younger set to the outhouse.

In the one-room schoolhouse, the teacher wore many hats: teacher, custodian, nurse, and occasionally cook and counselor. Ruth was paid an extra stipend for janitorial duties. Her monthly paycheck amounted to $105.00, equivalent to about $2000.00 these days.

Arriving at the school early on bone-chilling winter mornings Ruth hurried to kindle a fire in the pot-bellied stove. Tucked in a corner of the schoolroom, standing close to five feet tall, the cast iron cylinder-shaped stove, baring its protruding belly, radiated plenty of heat to keep the learners warm and cozy. To fuel the fire that first year, cow chips (dried cow manure) were gathered in a big tub and burned, and those chips burned hot! The aroma of burning cow chips smelled like….dried grass of course!

Sweeping the floor and dusting were other chores on the list of janitorial responsibilities and were often assigned to some of the older students, who relished the tasks.

Fresh drinking water was transported to the school in a fifty gallon wooden barrel on a weekly basis via a wagon and team of horses. The driver of the wagon was a nearby rancher and the father of three of Ruth’s students. The water barrel was set behind a partition in the classroom, along with hooks for hanging coats. The water barrel was covered with a tea towel held in place by a removable metal band. One morning as Ruth approached the barrel to fill the drinking water bucket she noticed a small round hole in the tea towel covering the barrel. In Ruth’s words: “On investigating, I discovered a mouse floating in the water. I sent word to the rancher immediately. He came very soon and took the barrel away for fresh water. When he returned he quietly told me that when he got out of sight he took the mouse out and returned the barrel. He was known as a tease. I was sure it wasn’t the truth because he had three daughters in school.” In actuality, he had scrubbed the barrel thoroughly before refilling it with fresh water.

Wilson School was ahead of its time in one respect – the students had something warm to eat or drink for lunch every day. The flat top of the pot bellied stove was just right for cooking. Ruth credited her Aunt Sadie for coming up with the idea. According to Ruth, “Aunt Sadie thought that the kiddos that came in the covered wagon needed something warm. We varied from beans to hot chocolate, all furnished by Auntie. For years I didn’t enjoy hot chocolate. Making it and smelling it for so many years stayed with me.” In addition, parents of the students sometimes chipped in with a contribution of homemade chili.

Typically the school day began at 9:00 am and continued until 4:00 pm. The bus driver kept a close watch on the weather forecast; if there was the slightest chance of changing weather conditions, he came by an hour early to pick up the youngsters.

Ruth was licensed to teach grades one through eight, but every grade level was not represented. Students graduating from the eighth grade at Wilson School continued their high school education at either Kiowa or Maxwell.

Ruth was responsible for all of the discipline in the school. Students were required to be silent unless working with the teacher or assisting another student. Older kids were often asked to assist the younger ones. Out of respect for authority, it was considered extremely important for students to raise their hand if asking or answering a question, and to stand when the teacher called on them. Ruth emphasized that she and her kiddos got along fine; rarely was there any wrongdoing. Most of the time all it took was a stern look from Ruth as a measure of discipline.

The curriculum was basic. All subjects were taught, but science was lightly focused on. The main emphasis was on reading and English. The Wilson School operated under the auspices of the Colfax County Board of Education as did all rural one-room schools in the county. School supplies were plentiful, including chalk, board erasers, textbooks for each grade level, a plethora of paper, especially the coveted Big Chief tablets, crayons, and pencils. Books for reading enjoyment were checked out from a lending library centrally located in the County Superintendent’s office in Raton. The playground was bare of the usual equipment but students were resourceful, using their imaginations to invent or think up their own sources of amusement during recess breaks. Of course, they also played some traditional outdoor games such as Red Rover, Kick the Can, Tag and Hide and Seek. Jump rope and hopscotch were favored by the girls, while the boys enjoyed marbles and tops. On bad weather days, when the recess break was spent indoors, students played Tic Tac Toe and Hangman on the chalkboard.

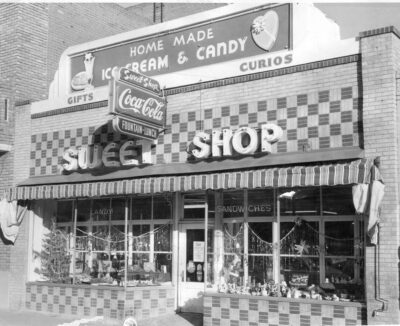

According to Ruth the school “was the center of the ranching community”. It served as a meeting place for the church and for pie suppers. The pie supper, held at night, was a combination of social and fundraising events. Pies brought by each school family were auctioned to raise money to buy Christmas gifts for Ruth’s students. Often the presents purchased were practical, rather than frivolous, such as a new toothbrush and a tube of toothpaste.

After leaving Wilson School, Ruth went on to have other educational adventures at a pair of other one-room schools, namely Kiowa and Vermejo Park, plus the coal camp town of Dawson. She capped off her career in the Raton Public Schools.

Biographical Sketch

Ruth and Franklin Saunders, in their home on South Fifth Street, circa 1975

Ruth was born in Raton on May 6, 1909, to Ed Brown and Dove Johnson Brown. At the time of her birth, Ruth’s family was living in Chico, New Mexico, where her father was engaged in the business of breeding and raising thoroughbred Hereford cattle. Her father passed away in 1917 while the family was living in Maxwell, and her mother relocated the family, comprised of Ruth and her brother Vestal, to Denver, Colorado, where the siblings received most of their education. Unfortunately, having to adapt to new economic circumstances, due to a nationwide depression, brought the family back to the Raton area. Ruth was working at the local JC Penney store when a friend suggested that she apply for a teaching position at the Wilson School. She was given the opportunity to fill the vacancy and accepted the job, launching the beginning of her successful teaching career in Colfax County.

She met her future husband, Franklin Saunders, manager of the Phelps-Dodge Mercantile while teaching at Dawson, New Mexico, and three years later he followed her to another educational adventure at Vermejo Park. Ruth and Franklin were married at Vermejo on December 23, 1939. They lived in Vermejo for a couple of years and then moved on to Morenci, Arizona where they welcomed their son Eddie.

Homesick for New Mexico, the Saunders family soon moved back, making Raton their permanent home. Ruth resumed her teaching career and Franklin became a successful businessman, initially operating an auto parts store and later a men’s clothing store.

In 1987 Ruth lost two very dear family members – her beloved husband Franklin, and her highly esteemed brother Vestal Brown. Ruth passed away in Tarzana, California on August 26, 2006, at the age of ninety-six.

Pat’s Personal Memory of Ruth

It was a warm Sunday evening in August 1971. My landlady had invited me to dinner. It was a delicious meal, but I had very little appetite. I pushed my food around on my plate as my thoughts wandered. My mind was fraught with apprehension as I nervously anticipated the onset of my career in teaching. The next day, Monday, signaled the beginning of the school year in Raton, with the usual scheduled teacher meetings. On Tuesday, as a brand new teacher, I would meet my very first class of students.

I had arrived in Raton a few weeks earlier from the small town of Aguilar in southern Colorado to embark on a career path that spanned thirty-three years. I came on board with a lot of “book learning” but I was short on practical experience. I was as green as grass as the saying goes – unsophisticated, extremely shy, and lacking in interpersonal skills, those necessary skills needed to communicate and interact with others effectively. This would be the first (and only) job that I ever held.

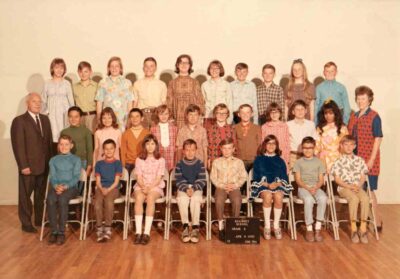

My landlady was Ruth Saunders, who fortunately for me, also became my teaching mentor. The 1971-72 school year at Kearny Elementary School teaching sixth graders was the sunset of Ruth’s career, while I on the other hand, in charge of a first grade class, was at the dawn of my life’s work. As a mentor Ruth provided guidance, emotional support, constructive feedback, and doled out sage advice, always in a positive, non-judgmental way.

Most importantly, Ruth was an exemplary role model. She demonstrated professionalism by the way she dressed, spoke, and respectfully treated others, namely her students, fellow teachers, and the parents of her kiddos, as she affectionately referred to her students. She did not resort to pettiness or criticism while off duty in the teachers’ lounge.

Ruth’s personality was marked by extreme calm and composure. Her unruffled spirit was an asset while maintaining discipline in her classroom. She seldom needed to raise her voice, especially when one of her “looks” would give the potential offender the incentive to “toe the mark”.

I am extremely grateful to Ruth for taking me under her wing, helping me, teaching me, and in general looking out for me. I feel that her time and effort with me contributed to the advancement of my professional growth as a confident, dedicated educator.

Following a twenty year stint educating first graders, I moved up the ladder a notch, to teaching second grade at Columbian Elementary School. During a special history unit of study, I invited Ruth to share her adventures of teaching in a one-room school – in particular, the Wilson School – with all of the second grade students and teachers.

Ruth sharing her memories of Wilson School with Columbian Elementary School second graders, circa 1990s

Ruth’s Heritage

Johnson Mesa (Photo by Jim Veltri)

“Tuesday Afternoon”, a painting of Johnson Mesa rendered by Raton artist Carl Swanson; owner: Cynthia Herndon

Sometimes referred to as the “top of the world”, Johnson Mesa is a significant tableland in Colfax County, in northeastern New Mexico. A short distance east of the city of Raton, Johnson Mesa, boasting an elevation of 8658 feet, is Raton’s signature landmark, so to speak, running about fourteen miles long east to west, and two to six miles wide north to south.

New Mexico Highway 72 travels across the mostly flat and treeless terrain. The cliffs surrounding the mesa are wooded, but the top is grassland. Dotted with several small lakes, the area is made to order for the summer pasturing of cattle.

Below the south rim of Johnson Mesa is Johnson Park, approximately six miles north of the TO Ranch Headquarters. About three miles long by two miles wide, with an elevation of 6800 feet, Johnson Park is ideal ranch property.

Johnson Park and Johnson Mesa were named for Elijah Johnson, a standout member of Ruth’s family tree. Lige, as he was popularly known, was Ruth’s maternal grandfather. At various times during her retirement years, Ruth delved into ancestral lore, sharing memories passed along from her “Granddaddy”. These memories were recorded and are part of news articles, a book on Johnson Mesa by Marianna Buhr, and oral history interviews by AAUW members, in a collection of information at Raton’s Arthur Johnson Memorial Library.

According to Ruth her grandfather Elijah “Lige” Johnson, was born on May 23, 1844, near Belknap, Texas at the forks of the Brazos River. During the Civil War, he served as a Texas volunteer in the Confederate Army. Following his service in the Confederacy, he married Martha Bragg at Belknap in 1865. A short time later the newlyweds left Texas for New Mexico Territory, lured by the reports of land open for settlement. Lige and Martha traveled in a covered wagon pulled by a yoke of oxen. It was an arduous journey and the Johnsons experienced their share of hardships, particularly the heartrending loss of a baby daughter, left behind in a tiny unmarked grave along the trail.

Arriving in Cimarron in 1867, the Johnsons found their hopes and expectations for a parcel of land dashed by Lucien Maxwell, arguably one of the most powerful men in New Mexico at the time. Instead of finding a vast expanse of free land waiting to be settled, they found themselves within the core of Maxwell’s “kingdom”, generally known as the Maxwell Land Grant. The Maxwell Land Grant, also identified as the Beaubien-Miranda Land Grant, was the largest privately owned abutting tract of land in the United States, comprising close to two million acres in northeastern New Mexico and southern Colorado.

Lige was hired on as a cowhand, working for Maxwell, but after a year’s time, he grew restless and decided to move on and find some land he could call his own. He gave his notice of leaving, stating that he wanted his own ranching operation. Maxwell advised Lige in no uncertain terms to pick an area east of Chico Rico, a boundary known today as Sugarite Canyon, because that region was outside of the Maxwell Land Grant.

In Ruth’s words, “Granddaddy chose the area now known as Johnson Mesa and Johnson Park. He built his home in the beautiful canyon below the mesa on the headwaters of the Una de Gato. The home of thick adobe walls and a shingled roof with a partial second story, and a large barn made of big hand hewed timbers were built there by Elijah Johnson. The hand made shingles used for the roof and exterior siding of the upper story were hauled by wagon from (the mining borough of) Elizabethtown, New Mexico.”

Two story ranch home built by Elijah Johnson at Johnson Park

(Photo courtesy of Mark and Debra Burk)

During the first spring at the Park, Native Americans came to a little knoll, not far from the Johnson Ranch, to carry on a ceremonial gathering of sorts. Lige separated a fat steer from his herd and gave it to his visitors. He continued this practice for several years, ensuring friendly relations with the local natives.

In 1870 the Maxwell Land Grant was sold to an English company. Elijah Johnson signed a contract with William Morley, an executive officer of the Grant, in 1873, sealing a deal for prime quality dressed beef at four and a half cents per pound. The meat was to be provided for the Ute and Jicarilla Apache tribes under the sponsorship of the Cimarron Indian Agency. The cattle were driven from the Johnson Ranch to Lucien Maxwell’s Aztec Mill in Cimarron where they were butchered and the meat was prepared and packaged for distribution to the tribes.

The bulk of Lige’s cattle were driven to market in Denver, Colorado. This entailed traveling through Raton Pass on a twenty-seven-mile toll road, operated by Richens Lacey “Uncle Dick” Wooten. Ruth shared a memory: “He (Wooten) gave Granddaddy a lifetime pass through the gate because he was the father of the first Anglo twins born in this area. My mother, Mrs. Dove Johnson Brown, and Uncle Mose Johnson were the twins.” Continuing in Ruth’s words, “On the return trips such supplies as brown sugar by the barrel, materials which were bought by the bolt and other supplies hard to find were brought by wagon from Denver. On one of the trips to Denver, Granddaddy bought an upright piano for the musician of the family, my Aunt Patsy. He bought a spring wagon to bring the piano home in as it would be easier on it having to travel so far over rough roads. A gentle team of horses was used to pull it. The team followed the wagon in front of it as there was no driver. It came through in great shape and was used for years.”

Inclusive of their infant daughter lost at birth, while traveling to New Mexico, six children were born to Elijah and Martha. Johnson Park was the birthplace of Martha (Patsy), in 1868, and Sarah (Sadie) in 1873, followed by the twins, Mose and Dove, in 1876. The last daughter, Emma, was born at the Park in 1883. Besides the four daughters and one son, the Johnsons also raised a niece, Elizabeth Aird, and a young homeless waif called Williams, found by Lige on the streets of Raton. Ruth recalled, “One day when Granddaddy was downtown, he saw a dirty ragged little boy playing a mouth harp. He asked the boy for a tune and the boy came back with a quick request for a job. So, Granddaddy got him some new clothes, took the boy to a barber shop, then got him a bath and took him home – they raised him until he was grown.”

Bit by bit Lige’s family was approaching the age at which youngsters typically attend school, and he became concerned about Raton’s lack of formal education in a traditional school setting. He sent his two older daughters to Trinidad, Colorado, to be educated by the Sisters of Charity, a Catholic religious order. In Raton, circa 1884, the Marcy-McCuiston Institute was founded. It was the first public school in the Territory of New Mexico, built and maintained by private funds. Elijah Johnson hastened to acquire a home in Raton. He purchased a former schoolhouse from Tom Stockton that had been moved to Raton and converted for use as a residential home. Lige was the new owner of five lots plus the six-room “townhouse” located at 524 South Fifth Street in Raton. From then on the Johnson family lived in Raton during the winter months, allowing the children to acquire a much valued education.

According to Ruth, her granddaddy was a talented storyteller. She related an example of one of his stories about her grandmother, Martha, and some friendly Native Americans.

“She (Martha) was alone at the ranch with the children when some Indians came to her door asking for ‘fire water’. She told them she didn’t have any, but one of the Indians noticed a whiskey bottle on the mantel. He went toward it and my grandmother quickly told him that it was medicine. Not believing her, he took the bottle and swallowed a big gulp of the contents. What a face he made, as the bottle did contain kerosene and rock candy for medicinal purposes!”

An unexpected, and disastrous, occurrence during the Fall of 1893 led to the demise of Elijah Johnson’s twenty-five-year cattle operation. As per usual he ran his cattle on the Mesa during the summer months, but out of the blue, an early blizzard dropped severe weather conditions, driving his cattle over a very high rocky cliff, killing them all. “That is what broke my granddaddy,” recalled Ruth, “He later told us how he tried to get loans, but no one would loan him the money to restock. It seems as though there was a nationwide depression along about that time and money was very short in supply”. Elijah was financially ruined. Soon after, Ruth noted in her shared memories, her Granddaddy moved his family from the ranch into their Raton home as a permanent residence. She said he “sort of gave up and never went back to ranching. He never owned another cow the rest of his life.”

Lige worked in a local butcher shop until he was ready to retire. He kept his favorite saddlehorse “Joe” in his backyard. “When Joe was hungry,” Ruth reminisced, “he would remind Granddaddy by stepping on the back porch and rattling the door knob with his mouth. It was a common sight to see Lige Johnson riding Joe to town to do his shopping.”

Martha Johnson preceded her husband in death by several years. He lived alone in the family home at 524 South Fifth Street until his death on May 3, 1923, at the age of seventy-nine. Family members found him in his special spot beside the cook stove, sitting in his favorite rocking chair, asleep in eternal rest.

In 1941 Ruth’s mother, Dove Johnson Brown, had the family home razed and replaced it with new quarters, built on the same five lots purchased by Elijah Johnson from the original Raton town site. In the course of time the brand-new residence, constructed of fire brick covered with stucco, was passed down to Ruth and her husband, Franklin Saunders. For over 100 years, Elijah Johnson, his immediate family and later some of his descendants lived at the South Fifth Street address. The property was sold to Leroy and Janet Valencia in 2001.

Residence of Leroy and Janet Valencia, 524 South Fifth Street, Raton. Ruth’s mother, Dove Johnson Brown, had this home built in 1941, on the same five lots purchased by Elijah Johnson from the original Raton townsite.

Although Mrs. Saunders was not one of my teachers at Kearney, I remember her and her husband quite well. I thoroughly enjoyed reading this story and learning more about the history of the Raton area.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this wonderful story and history of my dear home town.! Jerilee Teague Gott, Raton Class of 60’