Readers, take a moment and skip backward in time to nineteenth century Colorado Territory, circa 1870. Put yourself in a top of the line Barlow and Sanderson stagecoach coated in red with colorful yellow wheels, and packed at full capacity with riders.

The resplendent coach, drawn by six large mules, three blacks and three grays, moves at a brisk pace of ten to twelve miles per hour as it makes its way to the next relay station. Traveling from El Moro, Colorado, about five miles northeast of Trinidad, the coach bounces its way to “Uncle Dick” Wootton’s tollgate and stage stop tucked high into the Colorado side of Raton Pass. Passengers alight from the stage for a hot lunch at Woottons’s table, while “Uncle Dick” himself regales them with tales of his days as a trapper and military guide. The coach continues snaking its way over the tortuous twenty-seven mile Raton Pass road, heading for New Mexico, but this day a seasonal rain on the Pass makes the narrow winding road especially treacherous. The coach, twisting and turning, struggles to stay upright on the muddy roadway surface, lurching forward just in the nick of time as it comes dangerously close to the edge of an embankment. The steep and grueling climb finally ends as the coach begins easing downward to the base of the Pass.

Passengers breathe a sigh of relief as they reach New Mexico territory relatively unscathed from their hazardous trek over the Pass. During the rest of the trip, the passengers endure continuous heat, choking dust and loud and steady snores from a couple of fellow travelers, but other than that, the final lap of the journey is uneventful. No attacks from Utes or Comanches, or road agents looking for easy cash. It is dusk as the coach, bumping and swaying, approaches a three story tower of adobe rising from the prairie – hugging the edge of the foothills. It is a magnificent manse, known as the Clifton House, both a relay station for the Barlow and Sanderson line, as well as a hostelry. Passengers have the option of staying overnight in the spacious abode and catching another stage in the morning, or after a good meal continuing on their way. The passengers climb down from the stagecoach, stretching their aching muscles, while a couple of cattlemen lounging on the veranda give them the fish eye from under their wide-brimmed hats. A tantalizing aroma is wafting from the inside of the house. The evening meal is about to be served up in the large, comfortable dining room. The weary travelers wend their way up the wide stone steps to make use of several basins of refreshing warm water and towels, available to them in the entryway for washing away the trail dust. Out in the barn the mules are unhitched and led to their stalls, while other rested well-fed animals are backed into place. After a brief respite, including a tasty meal of stuffed cabbage and other delicacies, the stage and its passengers head on south towards Cimarron, New Mexico.

Back to Real Time

Getting back to real time… The Clifton House was a significant stagecoach stop on the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail. It was situated near the Canadian River, about six miles south of present day Raton, New Mexico. These days a smattering of stone slabs, once part of the house’s foundation, are about the only visible evidence of past lives at the Clifton relay station – in company with bits and pieces of crockery and glass, and traces of metal tools, rusted and broken, scattered in the prairie grass among the cow pies and ant hills.

It is from several notable recorders of Clifton House history that a fairly accurate picture emerges of the once renowned relay station, hostelry, and action packed center for social events and cattle roundups. Nell (Coates) Stockton, labeling herself as a “self-appointed amateur historian”, put together her reminisces of the Stockton family, as told to her by her husband Claude. Her son Alvin Stockton, a New Mexico state legislator, compiled some stories from his grandmother, Dove (Stout) Stockton. Others were Manville Chapman, New Deal muralist and writer for New Mexico Magazine, and Kenneth Fordyce, a published writer of historical lore.

Thomas L. Stockton

The saga of Clifton House was set in motion with the arrival of Thomas L. Stockton in New Mexico territory. Stockton, the designer of the Clifton House , was born on February 20, 1832 and grew up on a plantation in Tennessee. His Father, William Hayden Stockton, moved his large family to Texas prior to the Civil War. During the war they lived on a ranch near Fort Worth.

According to Kenneth Fordyce, when Thomas Stockton was about thirty-four years old he “had come up from Texas to the green pastures of northern New Mexico with his herd of cattle, liked the place, saw its possibilities, and stayed.” At that time there were no settlements between Cimarron, New Mexico and El Moro, Colorado. Nell Stockton, in her family memoirs, stated that Thomas L. Stockton “bought land from the Maxwell Land Grant Company. This deed is on record as of January 1869.”

Manville Chapman, in New Mexico Magazine, portrayed Tom Stockton as a man of vision who dreamed of building a spacious home with shaded porches, where cattlemen living in the region could gather to shoot the breeze on range problems or to relax socially with their families. Nell Stockton said he had in mind a “pretentious house”, which would also provide refuge in event of Indian attacks. She wrote, “He hoped to have a finer home than J.B. Dawson’s on the Vermejo or Lucien Maxwell’s in Cimarron or Uncle Dick Wooten or any others around. He remembered the lovely Stockton home in Tennessee.”

Tom Stockton built a small house on the west bank of the Canadian River to live in until the Clifton House was built. He started putting up his dream home in 1866 and finished almost single-handedly four years later. After two or three years of working solo on the construction of the huge structure, Tom received help from his father, William and his brother Mathias, who had followed him to New Mexico Territory by a little more than a year. His father and brother settled on places of their own in the immediate vicinity.

Sweat, Toil and Indian Danger

The Clifton House was made of sun-dried brick, commonly known as adobe. Fordyce said, “Thick adobe walls made deep windows and assured a pleasant cool atmosphere inside in the summer and warmth and protection from storms in the winter.” Construction of any kind of home, other than a simple sod house with a dirt roof, on the 1860s New Mexico frontier was riddled with complications, snags, and struggles, and often caused a drain on the finances. Nell Stockton wrote, “All of the windows, sawed lumber and thick, wide shingles for the high, pitched roof were hauled by ox teams from Leavenworth, Kansas, in huge freighter wagons down past Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River, then past Uncle Dick Wootton’s toll station, and over the twisting, tortuous Raton Pass road. Sweat, toil, and Indian danger…these were the cost of pretentious buildings.”

Most of the information about the Clifton House indicates that it was almost three stories high. The basement, which was used as a storehouse, was only partially below the ground, giving elevation to the main floor. The rooms were large and roomy. The ceilings on the main floor and the second floor were unusually high, making it a very tall building. There was a huge porch or veranda that ran around the front and sides of the two stories. Chapman stated, “There had been no scrimping in construction of the Clifton House. There was room for a man to throw off his boots without them bouncing back and hitting him in the face.”

While Tom Stockton was building Clifton House he considered the possibility of Indian raids in northern New Mexico. He had the foresight to provide some precautionary safety measures in anticipation of possible raiding by the Utes or Comanches. Therefore, his plans called for the new house to be built around the old house and well, providing a water supply. Also, the house’s thick adobe walls and a basement full of provisions alleviated the worry of being compromised by a surprise attack.

Relay Station and Hostelry

Soon after the Clifton House was built, it was leased by Thomas Stockton, as a Santa Fe Trail relay station, to the Barlow and Sanderson Stage Line. Barlow and Sanderson already had a couple of relay stations up and running on the mountain branch of the trail – one at El Moro, near Trinidad, Colorado, and Uncle Dick Wootton’s Ranch on the Colorado side of Raton Pass. Stations were also planned for Cimarron and Crow Creek, which left Clifton House as the remaining place where a stage stop was needed. Barlow and Sanderson attempted to build their stations about twelve miles apart.

Barlow and Sanderson built barns and corrals, a blacksmith shop and other outbuildings. Nell Stockton penned, “When the stage arrived, fresh horses were waiting, and tired horses were unhitched and led to barns to feed and water. The fresh horses were hitched to the stagecoach and off they went again. Passengers paid twenty cents a mile and sometimes had to get out to walk up hills. The hotel part of the Clifton House and the bar were leased out to other people most of the time. Later the bar was moved to another building.” Sometimes the passengers rode in coaches drawn by horses, as Nell Stockton mentioned, but most of the time it was four to six large, powerful mules that kept the coaches moving along the specified course.

Trips by stage were timed so that the coaches arrived at Clifton House at mealtime or at nightfall. Passengers were given the option of staying overnight or continuing on their journey immediately. The stage runs experienced little delay in changing horses or mules. The tired animals were quickly replaced with fresh, well fed animals.

The front room of the Clifton House was leased for the company’s office, and the bedrooms, dining room and kitchen were contracted for feeding and lodging the passengers. Passengers on the stages stopped at Clifton House for meals or to stay overnight. There was sufficient sleeping quarters, since passengers did not mind sharing a room with others in order to get a good night’s sleep. There were two large bedrooms upstairs, one for men and one for women, dormitory style with five to six beds in each room. There were four bedrooms on the ground floor, two of which also had several beds to accommodate any large groups of passengers that showed up.

The service travelers enjoyed at the Clifton House was a memorable part of their journey across the Santa Fe Trail. In addition to comfortable beds, the spacious Clifton House dining room offered fine foods and tasty dishes to satiate the appetites of the passengers. Stuffed cabbage, dished out on Bombay China dinnerware, was the house specialty. Most of the food served to the guests was home grown, but occasionally luxury foods were imported from back east via the railroad. At that time the railroad ended at Leavenworth, Kansas so these foods had to be hauled from Leavenworth to Clifton House by wagon.

By the 1870s Clifton House had become a hot spot for people and happenings. Besides accommodating the stagecoach passengers, the hotel served as a meeting point for a myriad of social events, including weddings, parties and dances. One example was the wedding of Thomas Stockton’s brother, Mathias, and Miss Dove Stout on August 22, 1872, a grand celebration attracting guests from miles around. Additionally, Clifton House was the headquarters for cattle roundups, providing the means for northern New Mexico cattle men to brand calves and sort out steers targeted for market.

By 1872 the area around the hostelry and relay station grew into a settlement known as Clifton, according to Fordyce. Nell Stockton wrote, “There was the post office, the land office where claims could be filed for government land, and of course a store where travelers could replenish their supplies. There is a little cemetery on the hill to the west, and sometimes people have come from far away to visit these graves.”

Although permanent structures for the amenities of education and religion were missing from Clifton, there were some sporadic attempts made to provide for the spiritual needs of the people. Alvin Stockton, recollecting stories told to him by his grandmother, stated, “No regular church services were held at Clifton but Episcopal and Methodist ministers often came through and held church. Large crowds attended these meetings, often more out of curiosity than a longing for the spirit. Catholic priests also held services at times. Neither was there any school at Clifton. Those who had sufficient means sent their children to Trinidad or elsewhere for their schooling.”

Undeserved Reputation

Clifton House gained a reputation, arguably undeserved, of being a stopping place for unsavory characters. Chapman said, “For some vague reason many chroniclers of the past have talked of the Clifton House as being a ‘notorious’ hangout for cutthroats and thieves who preyed on the innocent stage passengers, robbing them and burying their bodies in a ‘boot hill cemetery’ up back of the place.”

Chapman, emphasized in his writing that there were actually only two killings at Clifton House. The first shooting at Clifton House was a case of mistaken identity. While trying to apprehend the gunfighter, Chunk Colbert, a sheriff from Trinidad, Colorado accidentally killed a waiter at the hotel who had come west for his health. On January 6, 1874, another gunfighter, Clay Allison and Colbert faced off at Clifton House, with Allison securing the victory. Colbert was reportedly buried in Clifton’s little cemetery.

Nell Stockton’s husband Claude, at the tender age of four, was an innocent bystander during the killing of Chunk Colbert. She recorded the story in her memoirs, “The notorious Clay Allison rode into the settlement one day with two other men. They hired a native woman to cook a meal for them. Claude and his father had gone to Clifton in the wagon that day to buy a new stove. A new baby was due to arrive and they needed more heat in their home. Claude was seated high up on the wagon seat facing the cabin where the three men had just gone in, and his father had just loaded the stove when three shots rang out. Clay Allison came out of the cabin with a smoking gun, leading one young man by the wrist. The other one of his companions lay by the table in the cabin. Everyone darted for cover, no one wanted to be a witness, or he might be next.

Claude’s father took the reins of his horses and whipped them up to get away as quickly as possible. Claude kept saying, ‘Man shoot man,’ with his father trying to hush him up. Clay Allison and his remaining friend rode away but some time later, the second man’s body was found.

When the stove was unloaded at their home, it was found that there was no stovepipe. They had forgotten it in their hurry to leave Clifton, and would now have to wait until all the excitement blew over before returning.”

Short, but Glorious Existence

In the late 1870s reports came that a railroad was being built, and it was getting closer as time went on. This was troubling news for the stage company because there would soon be no stages or travelers to use the Clifton House. In 1879 the tracks of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroad reached Otero, a few miles north of Clifton. Nell Stockton noted, “The railroad was built almost by hand with the help of mules and iron scrapers and picks and shovels.”

The country was becoming too crowded for the builder of the house, Thomas Stockton and his father William, so a few years after the arrival of the railroad, they loaded their belongings in a freight car and relocated in Arizona, just across the line from Silver City, New Mexico. When Tom Stockton was getting ready to leave Clifton a celebratory picnic was held in his honor. People came from miles around to bid him farewell and “a fine time was had by all of the old friends” according to Nell Stockton. William Hayden Stockton died in Arizona in 1890 at the age of eighty-one. Thomas L. Stockton died in 1902 near Silver City.

The Clifton House had a short but glorious existence. With the arrival of the railroad, Clifton House lost its importance and standing and was soon deserted. Time, weather, vandals and treasure seekers, and a devastating fire in the mid 1880s have pretty much erased all physical vestiges of the once impressive adobe manor. The house is gone, but the memories live on!

Clifton House’s Signature Dish: Stuffed Cabbage

1 ½ lbs. ground chuck

1 tbsp. cornstarch

1 tsp. salt

1 tsp. ground nutmeg

1 tsp. ground black pepper

3 tbsp. milk

1 egg

2 onions, finely chopped

1 tsp. caraway seed

1 29 oz. can of tomatoes

1 3-4 lb. cabbage

cheesecloth

To prepare the cabbage: cut a cover out of the bottom about the size of a small saucer, with the stem forming the center. Scoop out the center of the cabbage making a large cavity.

In a bowl combine the meat, cornstarch, spices, egg, milk, and one tomato chopped fine with one of the chopped onions and place in the cabbage. Replace the lid, and wrap tightly in the cheesecloth. Place in a large kettle of boiling salted water and simmer until done, anywhere from one hour to an hour and a half. The time will depend on how dense the cabbage is.

Saute the remaining onion in a little butter and add the remaining cabbage from the scooped out center and stir-fry until limp; add the remaining tomatoes and simmer until the mixture is reduced slightly. Season to taste. Serve on the side and ladle over the cabbage when done.

Serves four to six

Preparation time: about forty minutes

Cooking time: 1-1 ½ hours

(Reprinted from the archives of The Raton Range (6/27/198

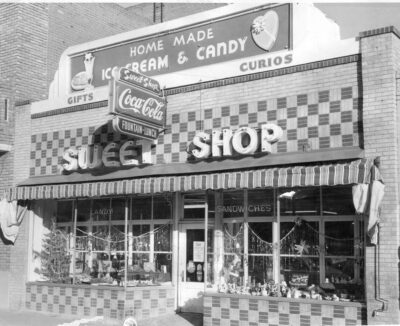

The Clifton House in its hey day. All of the windows, sawed lumber and shingles were hauled to New Mexico by ox teams from Leavenworth, Kansas along the Santa Fe Trail. Photo is courtesy of Christy Norris