A bolt of lightning flashed across the sky, accompanied by a rumble of thunder somewhere in the distance. Gently falling rain pitter-pattered against the front window of the truck as it toodled along the road. A family of five was crowded, sardine-like in the cab of the truck. The truck inched its way up a hill as it headed for the coal town of Koehler, NM, tucked away in the Crow Creek Valley, about 22 miles southwest of Raton, New Mexico. Carolyn, age three, wedged between her brothers Kenny and Johnny, felt a churning in her pint-sized stomach as the truck lurched forward steadily climbing its way into the canyon. In her child’s mind, it felt like the truck was scaling the highest mountain, instead of merely advancing to the top of a hill. Carolyn was frightened. “Where are we going? Why did we move?” she wondered to herself. She longed for her familiar, comfortable life back in New Brilliant, formerly the Swastika Coal Camp.

That rainy day in 1945 – Carolyn Volpato Woodul’s earliest memory of the Koehler Coal Camp – marked the beginning of her father’s subsequent transition from labor to management in the coal mining industry. Previously he had been cutting props in New Brilliant. After the move to Koehler, he initially worked in the mine and was a card-carrying Union member. Before long he was promoted to Supervisor of the Koehler Mine.

Woodul says her father was especially adept at languages and became proficient at several, including English, Italian, and Spanish. He also mastered enough of the Greek and Slavic languages to converse effectively. Arguably his linguistic competence helped him out immensely in his supervisory role, allowing him to communicate with the miners under his charge in the culturally diverse surroundings of Koehler.

The Birth of a Coal Camp

Koehler was one of the seven sister camps that were part of the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific partnership. The town claimed its name from Henry Koehler, a banker from St. Louis, Missouri, who was a major investor of the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company and also the company’s first president. These days Koehler is one of several abandoned coal camp towns situated on the spectacular Vermejo Park Ranch property, owned by media mogul Ted Turner.

The Swastika Fuel Company, a subsidiary company controlled by the St. Louis, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Company, opened its first mine at Koehler in 1906. It was an instant success. At its peak, the town boasted a population of about 1800.

Koehler closed in 1924 but re-opened twelve years later on a limited scale. In 1952, Koehler shut down almost completely, forcing most of the town’s inhabitants to move away. Kaiser Steel Corporation purchased Koehler in 1955 and continued to operate the mines with skeleton crews until the late 1960s.

Settling In

Once they arrived in Koehler the Volpatos, a second-generation Italian American family, inclusive of parents Enrico and Gemma, and children Johnny, Carolyn, and Kenny, immediately moved into one of the typical camp houses. Their home, perched on the top of a hill, overlooked most of the other houses. The floor plan included a kitchen, living room, and two bedrooms, plus an extra room that was an add-on to the back of the house. As might be expected, the home was heated with coal. “We had coal heat, but the added room did not have heat. My brothers slept under lots of blankets. It was cold!” Woodul recalls. She continues, “We had indoor plumbing, but no bathroom. We had an outhouse and used catalogs. I don’t remember when we first had toilet paper.” Once her father was promoted to Supervisor, the Volpatos moved to the Superintendent’s house, which was the finest in Koehler.

While Wooduls’s father toiled in the mine, her mother worked at cooking, cleaning, caring for the children, managing the finances, and seeing to it that the family home ran smoothly. She, too, was multilingual, having a good command of Italian, Spanish, and English. Woodul describes her mother as the “ultimate child of the Depression”, a woman ahead of her time when it came to recycling, stockpiling, and curbing wastefulness. “We were never allowed to waste any water,” Woodul remembers. “I always helped her do the laundry and she would use the water for three loads. We would take out the first, put in the second and then the third. We had a crank washer and that wasn’t too bad. When my mom got her first electric washer, she did the same thing no matter how much I fussed at her. As a child, she had carried water for washing from a nearby lake in Maxwell, and could not bear to waste water.”

Always Be Prepared

Most Saturdays the family drove into Raton where Woodul’s mother spent the day shopping for necessities. “I learned quickly how to shop and what one should pay for flour, sugar, and anything else. My mother knew the price of everything. She frequently corrected the clerk! When coupons became available, she used coupons for everything. I still do that!” Woodul says.

Accumulating supplies for future use and recycling items like foil, wax paper, and bags were also habits passed on to Woodul from her mother. She says, “My mother stockpiled everything. We never knew if we would get into town. As a result, I do the same thing. We live on a mountain and I stockpile when I find sales. As a result, there was no rush to the stores to purchase toilet paper or food when people started to panic during the coronavirus.”

Coming from a long line of “avid gardeners”, Woodul’s father used his gardening savvy to plant a sizable garden, harvesting a bounty of homegrown produce annually. Asparagus, rhubarb, Italian green beans, peas, onions, lettuce, radishes, and zucchini were some of the variety of vegetables making their way from garden to table. She recalls, “What we did not eat fresh, I helped my mother can and later freeze. My favorite thing was Italian green beans and we would eat them all year long.”

It’s the Little Things That Make a Home

The ladies in the camp were members of the Home Demonstration Club, and Woodul remembers that each time they met the family was likely to have “a new kind of dinner”. “My father was a picky eater and wanted meat, potatoes, Italian food, and a few other things, but my mom sneaked in new casseroles and side dishes. We sat down for dinner every evening. My father was served first; he had worked hard all day. The children ate next and my mother would frequently say, ‘I am not hungry’ if food ran short. We always had dessert – a cake, pie, or cookies. We never wasted anything,” she says. Her father’s lunch box was filled with meat, bread, fruit, and some type of sweet when he left for work each morning.

Woodul’s clothes were nice hand me downs, and she was allowed only one pair of shoes at a time. “I mostly wore hand me downs from my mother’s friend. Her daughter had nice clothes so it was just fine. My mother shopped sales and shopped for clothes at Rubin’s store. We wore dresses to school no matter how cold it was,” she recalls.

Work Hard, Play Hard

Most people worked hard and looked forward to time off to enjoy life’s simple pleasures. Visiting with neighbors was a popular pastime. Woodul’s father and his friends enjoyed making wine. “A train car would come to Koehler with a load of grapes. All of his friends would get together and make wine at each other’s houses. It was quite the celebration,” she says. Her mother had a group of friends that made a weekly trip to Raton on Wednesdays to see the latest movies. The movie theater conducted cash drawings and “sometimes one of them would win some cash”.

Woodul’s family attended weekly church services at the Catholic Church in Maxwell where her grandmother lived. “We attended Mass and had lunch and spent all day there, often getting home after dark. That farm supplied most of the meat we ate,” she says.

Once children finished their chores they had the run of the camp. Woodul recollects hiking, exploring nature, and playing outdoor games such as hide and seek, jacks, marbles, jump rope, hopscotch, and Red Rover, to name a few. “We crushed soda cans over our shoes and wore those. We played rubber guns with rubber bands. One of my fondest memories was acting out movies. Each person had a character. It became refined because seeing a movie was a rare thing to do, ” she says. Woodul and her friend Kathleen discovered a couple of horses on a nearby ranch. They would climb the fence and ride the horses bareback. “We never got caught or maybe it was okay with the rancher,” notes Woodul.

Living on a hill created the ideal setting for sledding, one of Woodul’s favorite winter activities. She describes the fun: “A couple of older kids built up big bumps in the snow so we would go flying through the air, then get our sleds and trudge back up the hill. We did that all day every day, as long as we had snow. We would come in and put our clothes by the coal stove and put on dry ones and go right back out again. My mother would fuss at me because she did not think I should be getting cold. At the age of two, I had a rare kind of pneumonia and stayed in the hospital from January 2nd until after the 12th, my birthday. My parents had been told I would not survive, but after my birthday I had a great turnaround.”

Schooldays

Woodul’s best memories of Koehler centered around her school experiences. She loved school! Early on, before formally starting school, she decided that she wanted to be a teacher. Perhaps she took a cue from her maternal grandmother who had been a teacher in Italy. Woodul pursued her lifelong dream and became an educator, racking up some impressive teaching awards along the way, and later earning the credentials for an administrative position. Woodul’s lifelong love of learning actually started a year earlier than it was supposed to. She says, “Because January 1st was the cutoff for starting school, and my birthday was twelve days later, my mom persuaded the principal to let me start school a year early. Quickly I was promoted a grade. When I out-spelled all of the third graders, the teachers wanted to promote me another grade. My mom said, ‘No’. The ironic thing is that I consider myself an average speller and have become very sloppy in my proofreading, especially when working on my phone.”

The original two-story schoolhouse in Koehler burned to the ground in 1923 and was never replaced. Instead, several 24 x 24 cinder block homes were converted into classrooms. Each grade had its own building and teacher. Woodul says she remembers there were “about four students in each class that were ‘Anglo’”. Most students had another first language. Hispanic students were not allowed to speak Spanish in the classroom or on the playground. This rule was strictly enforced. It bothered Woodul when she “heard students being chastised for speaking Spanish”. Years later, at a high school reunion, she experienced an aha moment – she learned from one of her school classmates that Hispanic parents asked for their children to be immersed in the English language. “As a former secondary teacher and administrator, I do not believe in English as a second language,” she states. She goes on to say, “I saw firsthand how well all of the students learned in those small mining camps. I have been able to see how successful those students became later in life. Full immersion worked really well. Having very tough teachers helped too. I especially remember my fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Rathbone. If anyone missed a question, she threw anything that was on her desk at the student. Books and erasers were what I remember most. I never had that happen; I was extremely motivated! I did have her as a piano teacher for two years. If I missed a note, she hit my knuckles with a ruler. Believe me, I practiced!”

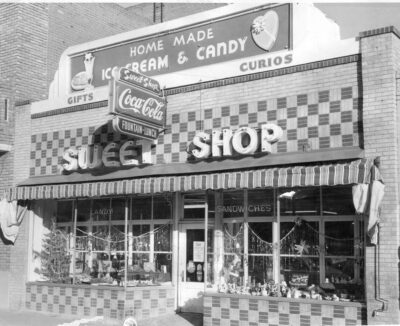

Woodul became a first-time job-holder when she entered the third grade. She was hired to pick up the mail for one of her favorite camp ladies – Jennie Baker – and collected a “salary” of fifty cents a week! “I was RICH!” she exclaims. “Most of my money went into my savings account in the bank in Raton, but often I would buy two peanut butter cups. They were two for a penny. The camp stores were owned by the mining company. At first, miners were paid in script so they would have to pay higher prices. Later they were paid in cash.”

Strike!

While still a schoolgirl, Woodul began to understand the distinction between labor and management. All four of her Italian grandparents left Colorado during the Ludlow Massacre, an attack on striking coal miners and their families by the Colorado National Guard and Colorado Fuel and Iron Company guards. The massacre, which occurred on April 20, 1914, at Ludlow Colorado, resulted in the deaths of twenty-five people, including eleven children. “When women and children were killed in a strike situation, my grandparents left Colorado,” she says. She states further, “On April 23, my paternal grandmother spent the night under a bridge in cold Colorado weather with her newborn son – my father. My maternal grandparents rode a train to Maxwell with a year-old son. My grandmother was pregnant with my mother who was born on July 23, 1914, three months after the April uprising.”

Much has been written and said about the eclectic array of cultures meshed together in coal mining camps. According to Woodul, “the owners of the mines made sure to have many cultures because they did not want the miners to be able to communicate with each other and work together to change mining conditions.” Referring to Ludlow she says, “Miners had rebelled about working conditions. It wasn’t really about pay, but about working conditions.” During Woodul’s time at Koehler, the dominant nationalities were Hispanics and Italians, despite the efforts of mine owners to recruit a mix of ethnic groups.

Woodul’s grandparents left Colorado during the strikes, but her father later became part of management, being a Supervisor of mining activities at Koehler. “My parents were registered Republicans. The minute my father knew there would be a strike, he came home, we packed and went to Denver to visit his sister. When the strike was over we came home,” she states.

Siren Call

Lurking in the background hidden deep within the daily hum of camp life was the anticipation of danger, an underlying anxiousness, and unease that was brought to the surface by the shrill wailing of a siren – signaling trouble in the mine. Cave-in, explosion, fire, runaway coal car? As the piercing noise echoed into homes, schools, the company store, and post office, those listening were gripped by a cold fear coupled with agonizing thoughts about who might be injured or dead. Is it my son, my husband, my father, my uncle, my grandfather? Woodul was in high school when the sirens were for her father, “My father had a coal mining car run over him,” she states. “It injured his hand and ran over his legs. As difficult as this is to imagine, he spent nearly a year in the hospital in traction.” Following a lengthy recovery, he was back on the job.

Some years later Woodul’s father was once again a victim of misfortune. While inspecting a part of the mine for potential safety issues, the roof gave way and he suffered an injury that was ultimately fatal. “I was a sophomore in college when a mine caved in and he survived for two days and passed away,” she sadly recalls. She continues, “My older brother Johnny was out of college; I was in college, my brother Kenny was a junior in high school, my sister Doris was eight and my little brother Bobby was four. A lot of that was a blur. I remember details, though, such as all of my former teachers were at his funeral and that meant so much to me. By that time we had moved to the Superintendent’s house in the camp. It was the nicest house. Because my brother was a junior, the decision was made to allow my mother to stay in camp housing until he graduated a year and a half later. Usually, widows had one year to move and sometimes had to leave as soon as possible. My mother moved to a farm in Maxwell that my parents had purchased years earlier.”

Memories Stay With You

Living and growing up in Koehler, Woodul was inspired by the example of a couple of adults in the coal town. “I have several heroes from that time,” she says, “first, Pete Maga. Pete was a co-worker of my father’s. Pete traveled on a boat from Italy at the age of nine. I cannot even imagine that.” She continues, “Another was Pauline Yaksich. When she was pregnant with her fifth child, her husband was killed in the mine. The company took care of her, which was rare. They gave her a house in Koehler, and she cleaned the schools. Recently her youngest and only surviving son (Judo) reminded me she arose at 4:30 am every morning to light the stoves for the schools and then of course cleaned each of the classrooms after school.”

Woodul honors and appreciates the memories of her life as a coal camp kid. Parents, teachers, and other coal town role models helped form her character and set the scene for her successful career path. “Personally I would not trade for my youth in Koehler,” she says. “I was happy, healthy, and learned to get along with everyone. The schools were good. Kids respected their elders and were good kids.”

Nowadays, Woodul lives on Barlett Mesa with her husband Jack, a retired airline pilot, and an ever-changing menagerie of animals.

All photos are courtesy of Carolyn Volpato Woodul

Carolyn, what a wonderful story. My grandfather died in the 1923 cave-in in Dawson. The family of 5 kids and mother moved to Raton soon thereafter so I didn’t know all the stories about life in a mining camp. When I went to the Dawson Reunion in 2016 a whole new world of stories opened up to me. I appreciate your sharing your camp life here.

Thanks, Beverly,

You have reminded me that I will attend the next Dawson Reunion. I have always wanted to do that. I am not sure how you are related to Mr. Krivokapich who was a coach at Raton High School. I always remembered that he was well-respected. Maybe I will see you at the next reunion.

Thanks so much, Jody. Our families were great friends. Did you know I played bridge with John, your Dad and my Dad. I was very impressed that knew how to play bridge.

Carolyn,

Thank you for sharing this wonderful story. It was very moving and real. I too, am proud to say I know the family and I miss living in Raton and spending time with the wonderful people there.

Bob Beaudette

Thanks, Bob, Arizona is not that far away. You need to come visit.

Excellent story about a great family an American success story that can be appreciated by all. I’m proud to have known the family and related by marriage.

Thanks, George Savage, our families melded well. My mom adored your mom. We always went to see her at work. That was long before Kenny and Judy got together.