Featured Image: Artist’s rendition of the prehistoric kill site, part of the Folsom Man exhibit at the Folsom Museum. (Photo by Jim Veltri)

The Carl Schwachheim Story

By Pat Veltri

In memory of Thomas (Tom) Burch, who diligently worked towards establishing acknowledgement of his uncle Carl’s contribution to one of American archaeology’s most significant discoveries.

December 10, 1922: “Went to Folsom and out to the Crowfoot Ranch looking for a fossil skeleton. Found the bones in arroyo ½ mile north of ranch and dug out nearly a sack full which look like buffalo and Elk. We only got a few near the surface. They are about 10 ft. down in the ground.” (Carl Schwachheim’s Diary)

The genesis of the significant role played by Ratonian Carl Schwachheim in the discovery of new information about the antiquity of man in North America can be traced to a December day in 1922 – when he and four of his friends journeyed to the Crowfoot Ranch, near the tiny village of Folsom, New Mexico. Schwachheim was born in Cantril, Iowa on January 13, 1878. In 1880 he moved to Raton with his parents Tom and Belle Schwachheim. He worked as a ranch hand and was a blacksmith’s helper in his father’s shop, but his fascination with natural history was his claim to fame.

In keeping with his interest, Schwachheim recorded his observations in a diary during the period of May 16, 1919 to July 4, 1929. His diary reflected his absorbing awareness of the flora and fauna of Raton and other places that he visited as well as a consuming curiosity about Native American artifacts. He often drew a small illustration of a plant, insect or arrowhead to clarify what he had written in his diary. In addition to recording the natural history of the area, he also collected specimens and artifacts. He explored canyons, mountain tops, caves and streams, as well as Native American ruins, mostly walking or traveling by horseback. He became an accomplished amateur naturalist.

Schwachheim was “Uncle Carl” to the late Tom Burch of Raton. Regrettably, Burch did not have the opportunity to know his uncle well. He was a youngster when Schwachheim was traipsing the countryside, observing, collecting, and recording. However, in an interview several years ago Burch easily delved into family lore, sharing memories passed along from his parents, of Schwachheim’s inquisitive persona, his love of the natural world, and his involvement with the discovery of paleontological evidence of early man in North America. Burch said of his uncle, “There was nothing that man wasn’t interested in. He had books from when he was about six or seven that were on a college level – a big set that somebody had given him back in Iowa, that covered fossilized sea life, nothing a child would usually read.” According to Burch, “there was nothing Schwachheim didn’t observe or collect or know about”, and he often wrote letters to experts pursuing knowledge, data or truth about a specific topic.

George McJunkin, an African-American cowboy, sparked off the interest that led to Schwachheim’s first trip to the Crowfoot Ranch in 1922. McJunkin, a foreman at the ranch, discovered a cache of large bones protruding from a wall of Wild Horse Arroyo some time after the 1908 flash flood near Folsom. One particular day McJunkin came into the blacksmith shop owned by Schwachheim’s father seeking help to get a wagon wheel fixed. As McJunkin waited for his wheel he became intrigued with an unusual fountain outside of the shop, which was topped with two massive sets of elk antlers interlocked with each other. McJunkin was impressed with the size of the horns. Burch said, “McJunkin was in the shop one day. They were talking and he told Carl that he found some bones that would fit those horns and that’s how that got started.” McJunkin gave Schwachheim detailed directions for getting to what he called the “bone pit” at Wild Horse Arroyo.

Even though Schwachheim kept McJunkin’s story about the bones in mind, it was still several years before he was able to look into exploring the “bone pit”. He did not own a car and a trip by horse and wagon would be laborious. In addition to Schwachheim, McJunkin told Fred Howarth, among several others, about his discovery of bones on the Crowfoot Ranch. Howarth, a friend of Schwachheim’s, who worked as an agricultural inspector for the First National Bank of Raton, was also interested in McJunkin’s bones.

Details are sketchy about how Schwachheim and Howarth happened to organize an expedition to McJunkin’s “bone pit” on December 10, 1922. According to Franklin Folsom, An Amateur’s Bonanza: Discovery of Early Man in North America, “…Schwachheim, no longer a self-employed blacksmith but a member and former organizer of the Brotherhood of Blacksmiths, Dropforgers, and Helpers, was on strike against the Santa Fe Railway, and hence had no job to keep him at home. Possibly he proposed the idea.” Accompanying them on the outing were Rev. Roger Aull, pastor of St. Patrick Catholic Church in Raton, James Campbell, an amateur taxidermist and Charles Bonahoom, a local grocer. Aull and Howarth both owned cars which made the trip easier. Sadly, McJunkin became ill and passed away several months before Schwachheim and his friends planned their excursion to the arroyo.

The five men gathered a gunnysack full of the bones to take back to Raton. Schwachheim and Campbell spent an evening in the kitchen of Campbell’s home studying books on paleontology in an attempt to identify what animal the bones came from.

During the summer of 1925 Schwachheim corresponded with museum officials in New Mexico but failed to pique their interest in the the bones. However, when he communicated with the director of the Colorado Museum of Natural History he received a quick, positive response. In late January of 1926 Howarth had to deliver some cattle in Denver so he hired Schwachheim to help him. While they were in Denver they met with Jesse D. Figgins, Director of the Colorado Museum, and showed him samples of the bones. Within a few weeks, Harold Cook, honorary Curator of Paleontology at the museum, had identified the bones as an extinct species of Ice Age bison, Bison antiquus. Such an animal was twice as large as the modern bison, and upon reaching maturity would have stood from twelve to fifteen feet tall at the shoulder.

March 7, 1926: “Went with Mr. Figgins and Mr. Cook to look at the fossils on the Crowfoot Ranch. They say they are worthwhile…” (Carl Schwachheim’s Diary)

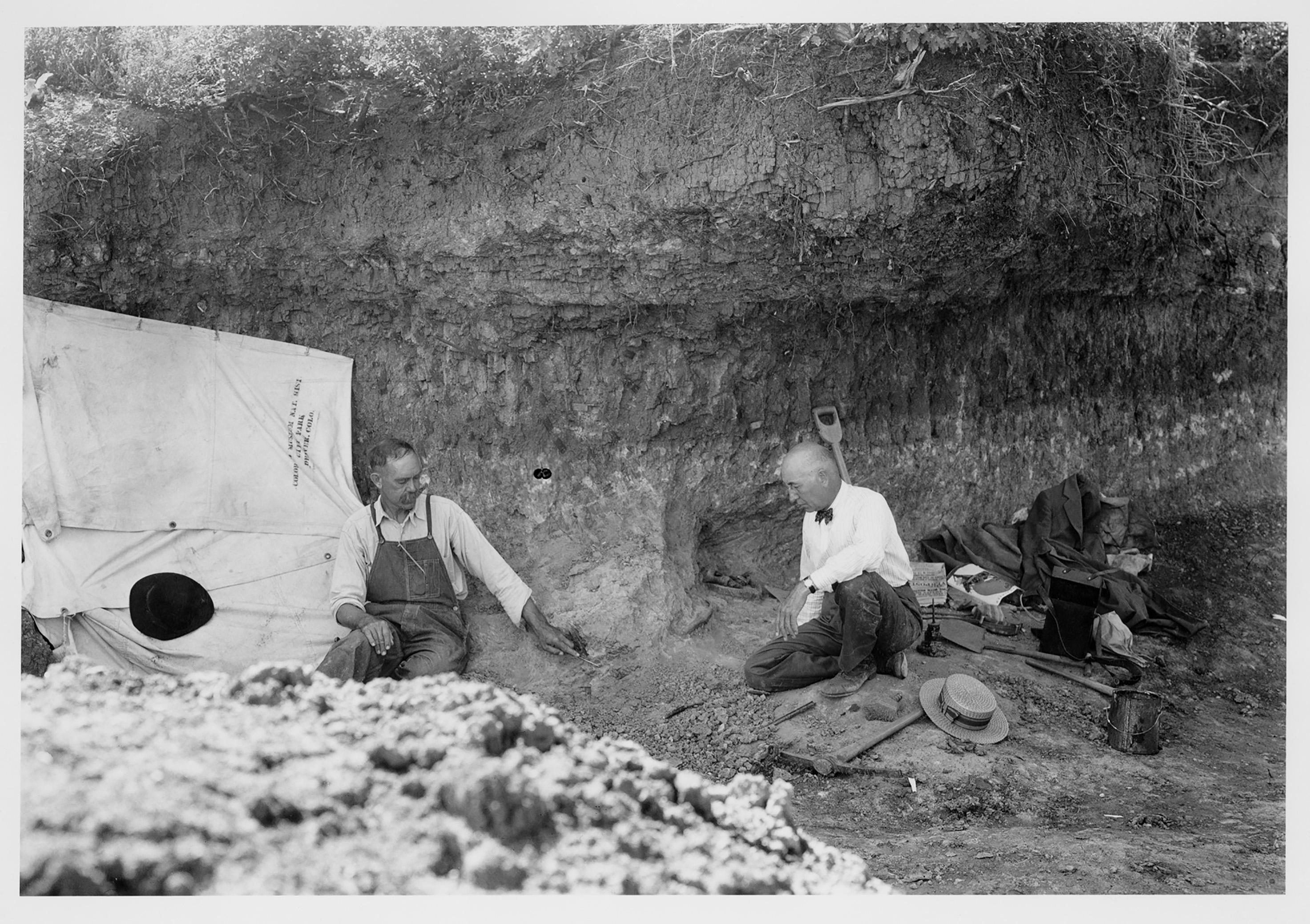

Figgins and Cook decided to visit the Folsom site. According to research by David J. Meltzer, Lawrence C. Todd and Vance T. Holliday, American Antiquity, Vol. 64, No. 1, 2002: “Cook and Figgins visited the site March 7, 1926, ultimately deciding to excavate with the aim of ‘supplying a mountable (bison) skeleton.” They hired Schwachheim to remove the overburden.” Meltzer’s research reported, “J.D. Figgins instructed Schwachheim to remove the overburden to withing a few feet of the bones over a large area, to ‘clear the ground for the recovery of the fossils in an orderly way.’” On May 2, 1926 Schwachheim arrived at the Crowfoot Ranch to begin work on the south side of the arroyo. By the middle of June, he was exposing bison bones from a prehistoric kill site. Figgins sent his son Frank to supervise the removal of the bones while Schwachheim continued working on the dig as his assistant.

July 14, 1926: “Found part of a broken spear or large arrowhead near the base of the fifth spine taken out. It is about 2 inches long and is of a dark amber colored agate and of very fine workmanship. It is broken off nearly square and we may find the rest of it. I sure hope we do. (drawing of artifact inserted) It is a question which skeleton it was in but from the position of them it must have been in the skeleton of the smaller one and just inside the cavity of the body near the back. It was found 8 ½ feet beneath the surface with an oak tree growing directly over it 6 inches in diameter showing to have been there a great length of time.” (Carl Schwachheim’s Diary)

The July 14th entry in Schwachheim’s diary marked the first find of a fluted projectile at the site. The point indicated superior workmanship. Though this was an important discovery, the point was not found in situ (in its original place). Meltzer stated, “The discovery was reported to J.D. Figgins in Denver who urged the crew to watch for ‘human remains and then in no circumstances, remove them, but let me know at once.’” Figgins cautioned them to sift carefully through the dirt, but they found no points in situ during the 1926 period of field work.

August 29, 1927: “…I found an arrow point this morning. It is of a clear colored agate or jasper. It is not exposed the full length but it is hollow on the sides and looks something like this (drawing of artifact inserted). The point was near a rib in the matrix. One barb is broken off… Sent a letter to the boss today.” (Carl Schwachheim’s Diary)

Schwachheim resumed his excavating tasks at the Folsom archaeological site in 1927. Work at the site expanded that year under the continuing supervision of the Colorado Museum of Natural History. Meltzer’s research reported, “Only this time the crew – as a result of an exchange J.D. Figgins had with Ales Hrdlicka in Washington that spring – was explicitly instructed to watch carefully for artifacts and leave unexcavated any spotted in place.” Hrdlicka, curator of the Smithsonian Institution’s Division of Physical Anthropology, following the then current thinking, vigorously refuted all claims that humans had arrived in North America earlier than 1000 B.C. Figgins had been viciously criticized by Hrdlicka for suggesting that the bison from the Folsom site had been killed by human hunters. Hrdlicka angrily contended that the Folsom points were not found in situ and could have rolled into the dig from the surface or washed into the site at a later time.

On August 29th Schwachheim drove his wagon wildly down the dirt highway leading away from the Crowfoot Ranch, dodging pot holes and leaving a cloud of dust in his wake, as he headed for the village of Folsom to mail a letter. This was no ordinary letter – it was a communication to J.D. Figgins with radical news. Schwachheim had found a projectile point near a bison rib, both still embedded in the soil matrix! Schwachheim managed to reach Folsom in time to send his letter on the evening train to Denver, setting in motion a chain of events that would forever alter the course of American archeology. Figgins in turn wasted no time sending telegrams to several prominent scientists, giving them the opportunity to visit the site and study the point. Meltzer noted, “Meanwhile, Schwachheim was urged to keep his eyes on the point ‘every minute and do not let anyone remove it or dig around it…regardless of who it is or what reason they give’”. On September 4, 1927 Figgins came to the site along with Barnum Brown, Vertebrate Paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History and Frank Roberts Archaeologist at the Bureau of Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution. A.V. Kidder of the Carnegie Institution of Washington visited the site on September 8th. All of these well-known scientists were in agreement that the point and the bison bones were contemporaneous, providing proof of human existence in North America by the Ice Age. (Whether by his own choice or if purposely ignored by Figgins, Ales Hrdlicka was noticeably missing from the eminent group of experts converging on the site, ready to share their authoritative opinions.)

In 1928 the American Museum of Natural History became involved with the excavations, “with Carl Schwachheim of this city in charge”, according to the April 18th edition of The Raton Daily Range. The Range’s article further reported that he was “going back this year as enthusiastic as ever”. By August the American Museum officials determined that the “bone pit “ was depleted. Three years of labor intensive work at the Folsom site had generated about fourteen fluted projectile points, give or take a few.

After Schwachheim finished field work at the site in 1928, he was invited to oversee the assembly of a bison skeleton at the Colorado Museum of Natural History. He was loath to do the job, according to Burch. Burch recounted in an interview, “My mother and my aunt Emily practically had to browbeat him to go to Denver. He didn’t want anything to do with those ‘damned tenderfeet’. They were so worried about getting their name on something. He took a dim view of their sincerity, but eventually he went up there and supervised putting the skeleton together.”

Schwachheim suffered from a heart condition and lived a brief two years following the completion of his field work at Wild horse Arroyo. He passed away on March 1, 1930 at the age of fifty-two.

Burch recalled, “I was so little I don’t remember him well, but he must have been very interesting. People who knew him say that a person could spend hours with him just talking; he could hold forth on so many different subjects and know what he was talking about. Not many people can do that.” He continued, “Everybody liked to come over to his house. It was just full of stuff that he had collected. He had a little museum going on with all of his collections, which included a massive arrowhead collection, Native American blankets and pottery, a butterfly collection, an assortment of bird eggs and skulls of animals. Anything unusual he had.”

There are an endless number of articles written about Folsom Man that downplay or ignore Schwachheim’s contribution to scientific knowledge about human antiquity in North America. Conversely, his correspondence with J.D. Figgins provides an irrefutable record of his persistence in persuading museum officials to take action regarding the bison bones. Additionally, his diary recorded vital details of the field operations. Since he was hired to work at the site, he also was responsible for a good part of the excavation. Without the benefit of training, he instinctively knew to remove the bones and artifacts in a careful way. Burch said, “He wasn’t college trained but he had everything right.” Of course his finding of a point embedded in the rib of an extinct 10,000 year old bison settled the searing controversy that man had occupied North America longer than scientists had previously assumed!

There is an important addendum to the Folsom Man discovery – the culture and pattern of living of this prehistoric man continues to be an archaeological mystery. Other than the projectile points excavated from the kill site, no other evidence of Folsom Man has been brought to light. Surprisingly, the hunting camp has never been discovered, which logically should have been situated near the slaughter area.

The Folsom site is currently under the auspices of the New Mexico State Land Office. The majority of the artifacts uncovered from the site during the late 1920s, including the in situ point spotted by Schwachheim, remain at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, formerly the Colorado Museum of Natural History. According to Steve Nash, Ph.D., Director of Anthropology at the Denver museum, “the iconic Folsom point is currently on display in the Prehistoric Journey exhibition with the block of sediment in which it was found.” The bison bones are not on display, but are stored in the museum’s research collections.

In 1999 curators from the Denver Museum of Nature and Science returned a Folsom point to New Mexico. The 10,000 year old spear point, unearthed from the original site, is housed in the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe. In the immediate area, The Folsom Museum has put together an all-encompassing exhibit focusing on Folsom Man, part of which features replicas of Folsom points and a small collection of bison bones gathered from the “bone pit”.