By Pat Veltri

Sad and lonely, deserted and abandoned, and mostly empty it has stood alongside the railroad tracks in Las Vegas, New Mexico for decades – a reversion to when train travel opened up tourism in the Southwest. The La Castaneda Hotel, situated along the former Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway, is about to receive a makeover. Plans are underway to restore the former Harvey House to the grandeur of the days that Ratonian Nina Strong remembers while working there as one of the famed Harvey Girls.

When Strong graduated from Roy High School in 1941 she had “sort of a plan” to go to college. However, it was the end of the Great Depression, there were four girls in the family, and money was tight. If she was going to attend college, she would have to work to pay her way. Her high school principal, who encouraged higher education for the students in his charge, became the catalyst for Strong’s enrollment in college. Soon after graduation, in the summer of 1941, he escorted Strong and her friend Josie Siedel to Las Vegas to tour the campus of Highlands University. Afterwards he treated them to lunch at La Castaneda. He knew the manager of La Castaneda, and with his recommendation, Strong and her friend were interviewed. That very day the two girls were hired as waitresses.

Strong accepted the job with the terms of thirty dollars per month pay plus room and board. “That was pretty good,” she says, “it was the end of the Depression and there wasn’t any money”. She went back to Roy, bought a footlocker, packed her belongings and moved into La Castaneda the next day. The bottom floor of the north wing of the hotel was set aside as a dormitory for the younger waitresses.

As a full time student working at La Castaneda, Strong’s schedule was grueling. She was assigned to work the 10:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. shift. After her shift was over, she usually slept for a few hours, and then walked to classes at Highlands. She grabbed a few more winks after school before starting the cycle all over again. Strong worked five to six and a half days per week, with Thursday evenings off to allow her to catch up on sleep.

La Castaneda was part of the Harvey House chain of restaurants and hotels located along railroads in the southwestern United States. For a period of years from the late 1800s to the 1940s, travel by train was the most common mode of transportation. The genesis of the Harvey House chain began with Fred Harvey, an English immigrant. While working as a freight agent for the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad, Harvey noticed the often crude facilities at railroad stops. He proposed the idea of establishing a system-wide string of hotels with restaurants to the Burlington railroad, but his longtime employer refused his offer. Subsequently the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway agreed to a partnership with him, and he opened his first restaurant-hotel in Florence, Kansas in 1878. Strong says, “He made a deal with the railroad that passengers traveling by train across the west would have proper food and a place to stay. They built all these hotels, about 150 to 200 miles apart, from St. Louis to California.”

Excellence in accommodations and food preparation quickly became synonymous with the Harvey name. Harvey expected his staff to keep up his high standards. Potential staff members had to come with a recommendation. Strong recalls, “No one was just hired that went in and asked for a job. You had to be introduced, you had to have a good reputation before you were able to go to work there and if there was ever anything derogatory about you, you didn’t stay.”

Strong received on the job training, mostly from another more experienced waitress, Kay Bradford. “It really was a very efficient type of organization. The organization part of it was that we did our job the way we were taught and we knew what we had to do, we did it, and it was just fine. If you didn’t, you went somewhere else, probably on home. They were very strict on how you did; you became practically invisible once you got on the floor and became a server,” she explains. In addition to her serving duties, Strong did quite a bit of side work such as making coffee and folding napkins.

The Harvey Girls at La Castaneda wore white uniforms, as did all staff members, with the exception of the hostess, who was attired in black. The uniform was akin to a nurse’s and included a white blouse with cuffs, white skirt, and white shoes and hose. The finishing touch was a black folded ribbon tie. Strong remembers, “The uniform was the starkest, whitest thing you’ve ever seen in your life! It was as stiff as could be. You could stand the skirt up.” The staff’s uniforms were washed and starched by the hotel’s laundry. “You had to be pretty neat all of the time,” states Strong. Waitresses “got the once over” before they went on the floor.

According to author Richard Meltzer (Fred Harvey Houses of the Southwest), La Castaneda “was named for Pedro de Castaneda de Nagera, the chief chronicler of Francisco Coronado’s expedition to the southwest from 1540 to 1542.” Meltzer noted that La Castaneda was designed by California architects, “using for the first time in New Mexico, Mission Revival style architecture”. Strong describes La Castaneda, built in 1898, as “beautiful with lots of fine furniture”. The dining room, where she spent a good deal of her time, had the capacity to seat 108 people, and the tables were set for gracious dining with linen, silver, crystal and china.

The outstanding quality of food served measured up to the genteel ambience created in the dining room. A network of local farmers and ranchers, and a Las Vegas dairy facility provided La Castaneda with meat, butter, milk, eggs and produce, assuring fresh food for customers’ gastronomic enjoyment on a daily basis. At some point La Castaneda also received fresh meat via Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe refrigerated rail cars.

Strong recalls that the portions of food served were more than ample. For example, there were four slices to a pie, instead of the usual six or eight. Chef Victor prepared most of the food, but there were also some assistant cooks. Strong remembers that Chef Victor expected the waitresses to place their orders according to his specifications, or run the risk of having their orders withheld.

Strong’s most memorable experience during her time as a Harvey Girl was serving the soldiers on troop trains during World War II. La Castaneda became one of the major meal stops for the troops and was arranged to serve hundreds of men at one time. Any open space was used, in addition to the dining and lunch areas. “We would know ahead of time when the train would be there and we had everything set up. Our kitchen had all the food ready and we could get them in and out in thirty minutes,” says Strong.

Strong deems her service at La Castaneda, from June, 1941 to August, 1942, as a “very good experience”, a time that helped her develop self-discipline, people skills, and a good work ethic, while partially realizing her dream of going to college. Even though Strong’s stint as a Harvey Girl was short lived – she gave up her job to marry – she and all of the many other “Harvey Girls” have earned their place in history. “We set a standard that hasn’t been met and it has followed us – we were the best,” she says.

The Fred Harvey chain sold in 1948. After World War II travel by air and by automobile increased in popularity in the West. As passenger travel on trains declined, business in the Harvey restaurants also fell by the wayside. Strong notes, “Along the same line, it wasn’t long before there were other nice hotels, and motels or inns came in.”

Lesley Poling-Kempes, author of The Harvey Girls (Women Who Opened the West), wrote that the fate of the closed Harvey Houses “depended on the Santa Fe Railway, which owned them, and on the interest among local residents which either protected them as historic landmarks, or forgot about them and left them to decay beside the tracks.

As for La Castaneda – after closing in 1948, it was privately owned over several decades by at least two different individuals. In 2014 it was purchased by Allan Affeldt, a real estate and technology investor based in Winslow, Arizona, and his wife, Tina Mion. The 118 year-old architectural gem is currently undergoing a $3 million dollar facelift, and Nina Strong is delighted!

SIDEBAR

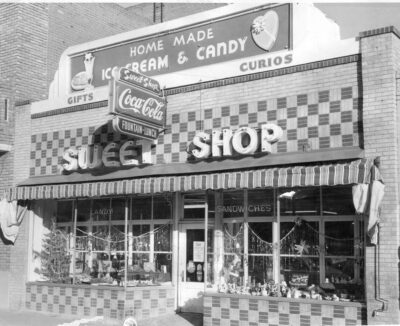

Raton’s Harvey House

Raton’s Harvey House, dubbed the Wallace Eating House, wasn’t in the same league as the impressive La Castaneda, but instead was just a typical dining facility by the tracks. The eating house, a small, red two-story frame structure located north of Raton’s Santa Fe depot, was built in 1882 and quickly became the social hub of the newly established community. During its short existence the eatery served railroad men, who had special meal rates at all Harvey Houses, as well as travelers, cowboys, and local businessmen.

A couple of the most distinguished patrons of Raton’s eating house were Senator Stephen W. Dorsey and his wife Laura. Dorsey, a Republican senator from Arkansas, left the Senate and Arkansas, amidst his suspected involvement in the Star Route Mail Fraud plot, and came out west in hopes of becoming a cattle baron. To that end he built a thirty-five room stone mansion, forty miles southeast of Raton. Possibly desiring to be part of some social activity, Dorsey and his wife purportedly made frequent trips to Raton where they found good food and accommodations at the Wallace Eating House.

Raton’s Harvey House had one important claim to fame – the very first Harvey Girls hired by the Harvey Company staffed the Raton location. Apparently before Harvey Girls, the company hired servers who were predominantly black men. This was an attempt to recreate the idea of train porters in starched white coats and black pants.

According to NM Harvey House Roll Call, Fred Harvey’s friend Tom Gable suggested that women replace the waiters. In 1883 while the two men were visiting Raton, they witnessed one of the usual brawls that periodically occurred between the waiters and rowdy clientele. Gable’s theory was that unruly customers wouldn’t punch a woman, especially one of high moral standards. Harvey hired Gable to move to New Mexico to manage Raton’s Harvey House, and the first group of Harvey Girls soon followed.

Gable thought the girls should come from back East, instead of being hired locally, because eastern girls would be more likely to instill some graciousness in the establishment’s disorderly, gun-toting customers. Roll Call reports, “Wanting to make sure these women would be respected, Harvey designed uniforms that combined the look of nuns and nurses.”

Raton’s Harvey House closed in 1903 because it was no longer needed. New Harvey Houses had been built in Trinidad, Colorado and Las Vegas, New Mexico.

Sources: Fred Harvey Houses of the Southwest by Richard Melzer

The Harvey Girls: Women Who Opened the West by Lesley Poling-Kempes

NM Harvey House Roll Call (Internet)

Photo of Raton’s Harvey House is courtesy of Arthur Johnson Memorial Library

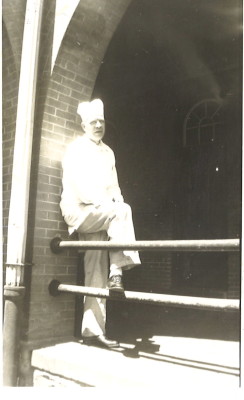

Other vintage photos are courtesy of Nina Strong

All of the stories you have placed on this site are so enjoyable, I want to thank you Pat. There is so much history in Raton and surrounding area.

So enjoyed, Pat! Thank you!

Pat, I love all of the historical pieces you have written about Raton and the surrounding area. Thank you so much. I grew up in Raton in the Fifties and still have such pride in my hometown. Thank you for digging out our history.l I have a special file in mt papers of your writings.

Keep up the freat work that you do.