In Fond Memory of Harriett (Hattie) Sloan

August 28, 1919 – February 12, 2016

By Pat Veltri

Picture it. War-torn England. 1943. Allied troops were preparing for the invasion of Europe, temporarily causing a lull in the combat zone. Four turbo-charged engines roaring in the English skies signaled the distinctive hum of a B-17 Flying Fortress. The massive bomber, minus the gunners who would ordinarily be manning the turrets, buzzed the 30th General Hospital before landing sedately on a small airstrip in the Midlands of England. A young Army nurse, attached to the 30th General, was escorted aboard. The Flying Fortress was Hattie Sloan’s “ride” to dance in nearby Nottingham.

First Lieutenant Harriett (Stech) Sloan was a wartime nurse, a heroine in olive drab fatigues, who ministered to soldiers, prisoners of war, and at times civilians, during World War II. As part of her service in the European Theater, Sloan confronted danger, dealt face-to-face with the sick, the wounded and the dead, and endured long periods of inactivity and boredom. Intervals of rest and relaxation and other light-hearted moments, like Sloan’s memorable “ride” to a dance, counterbalanced the hellishness of war.

Sloan, a native of northern Indiana, attended Milwaukee Downer, an all women’s college in Wisconsin after graduating from high school. Initially, she took core courses, with the goal of possibly becoming a teacher, but by her second year, she had switched to nursing and took all of the courses for the nursing program. During the spring of her second year of college at Milwaukee Downer, Sloan was accepted into the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in Baltimore, Maryland. Twenty-year-old Sloan was part of a group of sixty-five women who started nursing classes in the fall of 1939. “We were trained to be bedside nurses,” she explained. “The very first thing that we learned was how to change a bed with the patient in it. We learned about medicine, surgery, pediatrics, and other nursing procedures, much the same as nurses do today.”

Sloan had just started her third year of nursing school when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December, 1941. “By spring Johns Hopkins had assembled two hospital units to go into the war,” she said. “Those two units were sent to the South Pacific. Of course, after Pearl Harbor, the war in the Pacific was more immediate than the war in Europe.”

Americans were aware of the war in Europe before Pearl Harbor. “We knew the war in Europe was getting much worse, “Sloan said. There had been the blitz in England by the Germans, who were rapidly marching across Europe. We knew that ultimately the United States was going to go into the European war. Some of the Americans had already signed up for it but then it was evident that we were going to have to have a lot of military, so they had a draft for the young men.”

In the summer of 1942, Sloan and her fellow third year classmates assumed more responsibility with their on the job training because many of the regular nurses and doctors had gone with the Johns Hopkins’ team to the South Pacific. The Red Cross from Washington, D.C., came to Baltimore to recruit the student nurses for active duty in the Army Nurse Corps. Toward the end of that summer, after many serious discussions, Sloan and seven of her classmates made the decision to enlist in the Army. There was a bill before Congress to draft nurses. She said, “We felt obligated to go in, or they were going to draft us, so we signed up for the Army Nurse Corps to be together.”

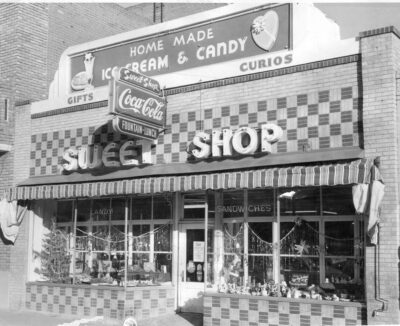

Sloan finished nursing school in October, 1942, and was inducted into the Army on November 1, 1942, at the drugstore across the street from Johns Hopkins Hospital. She and her classmates were assigned to Fort Belvoir, Virginia.

From early November until spring, Sloan and the other seven nurses worked on the wards. She recalled, “I was assigned to the medical ward where ultimately I got the measles, along with a good many soldiers.”

She went on to say, “One day my roommate Peggy Brooks saw a note on the bulletin board in the mess hall asking for people to go overseas. She signed us all up! That was in April of 1943. The first thing we knew we were being sent home on leave. I lived the farthest away and I only had a weekend leave. When I arrived back a t Fort Belvoir that Sunday night, I had to pack my gear to leave very early in the morning.”

That was the beginning. “From Fort Belvoir we went to Pine Camp, New York, where they weren’t even expecting us,” she said. “We found this was so typical of the Army. There were now thirty-five of us. We then went to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, which was the staging area to go overseas. When we first got on that train from Fort Belvoir we didn’t know where we were going. In fact, whenever we moved, they never told us where we were going. We had the blinds down and we’d peek out to see where we were. They were very careful about troop trains.”

At Camp Kilmer the nurses waited for a ship to take them overseas. “We soon got on the Queen Elizabeth which had been converted to a troop ship for 5000 people,” Sloan said. “We were going to England, which took five days. It was an interesting experience. We had bunk beds, twelve people to a stateroom and it was fairly rough so some people got sick. There were very few nurses on the ship. It was mostly male soldiers who all wanted to talk to us and date us. All nurses were female at that time.”

Bombs had destroyed many of the harbors in southern England, so the Queen Elizabeth docked in Scotland. The nurses were transported by train from Scotland to the Midlands of England, near Nottingham. The hospital was a brick building between Mansfield and Sutton-in-Ashfield. “Here we joined the 30th General Hospital because they needed nurses,” Sloan recalled. “We then took care of casualties, as well as many illnesses. Every night we could hear the bombers overhead. They would go really far for those days, clear to Romania to bomb the oil fields. Sometimes the bombers were shot down and that’s how the airmen became prisoners of war in Germany.”

In April 1944, Sloan’s unit was sent to Llandudno in North Wales for training. Sloan said, “We were billeted in private homes and we loved it. It was on the North Sea. The Army had set up mess halls and offices and our classes were in a Welsh church.”

While the allied forces were preparing to invade Europe, the nurses received instruction in gas decontamination, sanitation, aircraft identification, security, and map reading. Sloan remembered, “They also made us hike with hefty backpacks, making us hike as many as twenty miles. It about killed us and we complained bitterly! They were training us because they didn’t know what we were going to run into when we got to the continent.”

On June 6, 1944 – D-Day – the allied invasion of Normandy took place. Shortly thereafter, Sloan’s unit was moved near Bristol, England to a place called Pinckney Farm. “We were in tents and it rained and rained,” Sloan said. “We would hike and exercise but we didn’t have a hospital. We were just waiting and we did a lot of nonsense stuff to keep busy. World War II was often called ‘this waiting war’”.

Six or seven weeks after D-Day the allied forces still had not taken the land for the hospital. “When they made the invasion at Normandy, many, many people were killed, but they couldn’t push through the German lines,” Sloan said. “I don’t believe people realize how many weeks it took to take Normandy. Our hospital was intended to be a big hospital, 1000 beds in tents. They knew on the map where they were going to put it but they hadn’t taken the land.”

On July 21, 1944, Sloan’s unit was transported across the English Channel on a British ship. She remembered, “The English Channel was awfully rough. That night they had hammocks on the ship and we all had a lot of fun trying to get in those darn hammocks. There were no separate rooms; it was one big area. Some of the people were so sick because it was so rough. We went up on deck and the mist and rain made everyone feel better.”

Sloan continued, “We had this big pack on our backs. We went down a rope ladder off the ship and got into a landing craft because there were no harbors. We had to stand up in this thing. It was a craft that the front went down and we walked off of it into water up to our knees. The shore was on the Normandy coast and it was called Utah Beach.”

The unit was first taken to a convalescent hospital, and then transported by truck to a cow pasture, bombs and all! The Allies had still not taken Normandy. However, according to Sloan, “The big day was when they had the St. Lo breakthrough. We knew that something was happening. It started with small planes and the planes got bigger and bigger and they were bombing in the distance. They were pushing through St. Lo.”

After the St. Lo push through, the hospital was eventually set up in a farmer’s field. It accommodated 1000 patients and also included nurse’s stations, operating rooms, and quarters for all personnel to live in. It was an inclusive tent city, complete with a C-47 airstrip for the hospital.

Sloan remembered, “The first night we were open we received a 1000 patients. I remember there were Americans, Germans and Moroccans. The Moroccans wanted to kill the Germans so they had to put guards on the wards.” Sloan’s unit was in Normandy until the middle of November 1944.

They spent from the middle of November until two days before Christmas in Paris, where they were all detached to different hospitals. The war was moving on and eventually the 30th General was sent to Belgium to be near the Battle of the Bulge. There they took over a Belgian hospital north of Antwerp. For several months buzz bombs and V-2s were launched from Holland, only a few miles away. These bombs were intended to destroy the harbor at Antwerp but often fell all around the hospital and nearby villages. It was a bitterly cold winter with injured soldiers being shipped back from the front, many with frostbite.

Sloan reflected: “One of the saddest parts of the war for me was at this time. Being the nearest hospital, many Belgians from nearby villages were brought in to us. I still think of the little children who were playing near where the bombs landed, on cobblestone streets, and some did not survive.”

“The war was over in April 1945. We were gradually less busy and some of us were even sent on leave to the Riviera. Our turn to come home came in October when we came back to New York on the ship Argentina. All of our group chose to be dismissed from the Army Nurse Corps. We picked up our lives where we left off two and a half years earlier.”

Sloan and her colleagues in the Army Nurse Corps, with their skill, compassion, and dedication undoubtedly contributed to a decrease in the mortality rate among the military forces in World War II.

Wonderful story of such a great friend and special lady of Raton. The family is still missed, as

they made such a mark of well-meaning things during their years there. All were assets to the

community. Our good friends.

Thank you Pat. Lovely story. Hattie and all the family is missed in Raton!

Great story about an extraordinary woman! I was so honored to know her and will always treasure my memories of her! Thanks to Pat Veltri for yet another well-researched story about a local heroine!