By Pat Veltri

During a 1989 reunion of the 490th Bomb Group, in Reno, Nevada, Ratonian Albert (Al) Manfredi and his wife Tiny connected with several former crew members of the B-17 aircraft that he was assigned to during World War II. “What was left of our bomb crew was sitting at this table,” recalls Manfredi. “When we went in to where they were, this guy jumped up from the table, picked me up and swung me around; he scared the hell out of my wife. He told her, ‘This man – I’m here because he saved my life.’ It was our radio operator.”

Manfredi’s war time job was that of a ball turret gunner on the “Silver Meteor”, a B-17 heavy bomber aircraft. As part of a ten-man crew, Manfredi participated in thirty-five strategic high altitude bombing missions over Nazi occupied Europe.

On one particular bomb run Manfredi’s quick thinking saved the lives of the radio operator and a substitute waist gunner. He describes the circumstances: “One of our waist gunners went on sick call that morning so they always gave us another one to fly with so we’d have a complete crew. We were about to go in on the bomb run to drop our bombs and the radio operator noticed that this waist gunner that they gave us was down on the floor trying to get up. He (waist gunner) went to move around and he unplugged his oxygen. He didn’t realize that you couldn’t live up there (at high altitude) without oxygen. So the radio operator went back there to help him. You had a portable bottle of oxygen that you had to plug into the mask when you walked around. When he (radio operator) went back there (to the waist), he bent over to pick up this guy and plug him in, and his oxygen cable fell off so he was passing out too. There was a little window in the turret. I could look into the waist, so when I looked into the waist, they were both trying to get up. I could turn my door in the ball turret to where I could get up into the waist. I got up into the waist, grabbed my own oxygen bottle and went back and plugged them in.”

Manfredi, a native of Morley, Colorado entered the military service at the youthful age of seventeen, soon after completing his sophomore year at Trinidad High School. The aftermath of the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor was the driving force behind his early enlistment. Manfredi, along with eight other enlistees, from the Colorado towns of Trinidad and Aguilar, were sent to Fort Logan, a military installation eight miles southwest of Denver, for physicals and several days of aptitude and intelligence assessments. Although Manfredi signed up with the combat engineers, his testing results indicated he would be a good candidate for the Army Air Force. When given the option of remaining in the combat engineers or entering the Air Force, Manfredi, chose the Air Force because he felt that “it would be exciting to go up in the air”.

Manfredi, along with others, traveled from Fort Logan to Shepard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas for six weeks of basic training. Manfredi says, “We took our basic training there, and after we completed our basic training, we were sent to Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas, Nevada. We went to school there and trained there. They used to take us up flying to see if we could handle it. They showed us our .50 caliber machine guns that would be mounted in our turrets and we had to take them apart and put them back together again.” Another part of the training was marksmanship. Using a twelve gauge shot gun, trainees shot skeet and were required to hit twenty out of twenty-five clay pigeons to qualify for their wings. Manfredi recalls, “I think the first time I got four out of twenty-five. My shoulder was black and blue. Finally, I hit twenty-one out of twenty-five so I qualified.”

Once he received his wings, Manfredi was sent to MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida with a ten-man crew for more training that focused on getting pilots and crews comfortable with the B-17 Flying Fortress. “We flew with the same crew the whole time,” he says, “so we trained in Florida, flying with the crew.” Once this training was completed, Manfredi and his fellow crew members were sent to Newfoundland in “a brand new bomber”. “We flew from Newfoundland to Ireland non-stop. We were in the air for about ten to twelve hours. We were there one day and from there we flew to the 490th bomb group that we were assigned to.” The 490th flew missions over Nazi Germany, the Ardennes, Rhineland, and Northern France.

The 490th Bombardment Group (H), Eighth U. S. Army Air Force was a heavy bombardment unit stationed in Eye, a small town located in the northern end of Suffolk County, England, near the English Channel. The unit mounted attacks against enemy industrial and military targets. “We bombed industrial targets like marshalling yards, tank factories, aircraft plants, railroad yards, stuff like that. We didn’t drop bombs on people, never did,” states Manfredi. The 490th was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for a hit on a ball bearing factory in Merseburg, Germany. “We completely wiped it out with precision bombing,” Manfredi says.

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, a four-engine heavy bomber aircraft, capable of long distance travel, was primarily employed by the U.S. Army Air Force in the daylight strategic bombing campaign of World War II. The B-17 was dubbed Flying Fortress because it was outfitted with machine guns from tip to tail. According to the Internet source www.military factory.com, “the name ‘Flying Fortress’ is purported to have come from one of the reporters present during the unveiling of the machine at the Boeing plant, remarking as to how the aircraft looked like a 15-ton ‘flying fortress’.” Manfredi says, “There were twelve bombers to each squadron, and there was always three squadrons in a bomb group. There was a lead squadron, but you couldn’t fly behind each other in the B-17s because of the prop wash; if you got behind the bomber in front of you, it tossed you around.”

Typically, B-17 Flying Fortresses flew in what was known as the “box formation”. This formation allowed every gunner on board the aircraft to bring their guns to bear in any position needed. Gunner positions included a top turret gunner, a tail gunner, a ball turret gunner, a nose gunner, and two waist gunners. The flight engineer doubled as the top turret gunner while the bombardier and navigator in the nose section doubled as front (nose) gunners.

Manfredi, in his position as ball turret gunner, inhabited a Plexiglass sphere (turret) nestled in the belly of the B-17 that revolved a complete 360 degrees and was equipped with two .50 caliber machine guns, sights, and 1300 rounds of ammunition. The space was limited so he sat hunched, in fetal position, tracking enemy aircraft below, wearing only a safety strap for protection against falling out of the aircraft, should something happen to the turret in flight.

Manfredi recalls, “We used to fly about 35,000 feet. The Germans were very smart people; you have to give them credit. They had the radar and they had their anti-aircraft guns. They’d get your altitude and they’d set those anti-aircraft to burst at a certain altitude. If they didn’t hit you with one, they’d set it to explode at your altitude. The head on that thing was cast iron, but when it exploded it sent pieces all over. They used to come through the side of the bombers and it sounded like you were in a tin building and somebody threw a handful of gravel against the walls.”

He continues, “They put me in the ball turret because I was a small man; it took a small man in there. You couldn’t wear a parachute in there, but I used to wear a harness. We used to have to wear oxygen masks; they didn’t have pressurized cabins then. We put our oxygen masks on at 10,000 feet.” Because of the cramped quarters, Manfredi didn’t get into the turret until the bomber was over enemy territory.

Preparation for a bombing mission was lengthy. Usually the crew was rousted at 1:00 in the morning, given a snack and coffee, and then briefed on the day’s target. Briefing was intense and crew members focused on their mission.

While the air crew was briefed, the ground crew was conducting systematic inspections of every aircraft and warming up the engines.

After the briefing the crew retrieved their guns, installed them in the turrets, and then suited up in thermal clothing. Manfredi recalls, “You had to wear electrical heating suits because it was so cold up there. The electrical heating suit was like an electrical blanket on a bed. I think the coldest mission that I can remember was 60 degrees below zero. You wore nylon gloves underneath your heated gloves in case you had to take your big gloves off to work on your guns. The guns are metal, if you didn’t have that (nylon glove), and you touched the gun, your hand would freeze to the gun. We had good training.”

According to Manfredi, an interval of rest and respite was earned by the crew following the completion of a fixed number of missions. “We used to fly five missions and then they’d give us a 48 hour pass and we used to go to London quite a bit. When we completed twenty-five missions, they gave us a five day r and r leave to go to a hotel and rehab center in southern England.” Instead, Manfredi and his buddy purchased train tickets to Edinburgh, Scotland. “We went to Scotland for five days. A family took us in. They wanted no pay, but they used the ration cards that we were allotted to buy food. They treated us like kings. We really enjoyed it up there. I even have a picture they took of us in kilts; my buddy and I both got pictures. I’ve got it in my scrapbook. They treated us damn nice. That’s a good memory.”

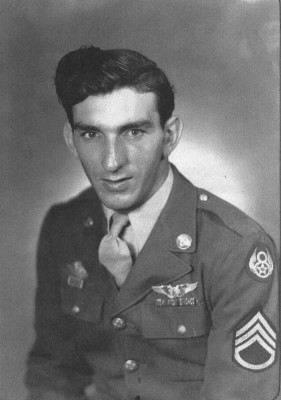

Manfredi mustered out of the Air Force on October 3, 1945 with the rank of staff sergeant and an impressive assortment of medals and citations for his bravery. In civilian life he worked briefly in the steel mill in Pueblo, Colorado, but mostly worked as a truck driver in California, Colorado, and New Mexico.

The combination of Manfredi’s small physical size and his immunity to heights and enclosed spaces placed him in the ball turret, one of the most hazardous crew positions in the heavy duty bomber. Even though he faced the risk of death time after time, his courage was unwavering, and he didn’t dwell on the possibility that he might not come back from a mission. “You thought about the things that you had to do. We all knew what could happen. We trained for that (bomb run) and that’s what we had to do,” he reflects.

However, the loss of three of his fellow crew members during bombing missions was a distressing memory that troubled Manfredi long after his discharge from the Air Force.

“The first one killed in our crew was the bombardier. One of those anti-aircraft shells burst and it took half his face because he was right up in the nose with the Plexiglas front. When he got hit, he pressed the intercom button and he was screaming. I never forgot that. I used to wake up nights when I got out. We lost three on our crew – the bombardier, the top turret gunner and one of the waist gunners.”

Manfredi, who turned ninety-one on November 25th, is the lone survivor of the Silver Meteor’s original ten-man crew. As he shared his war time memories, the pride in his voice showed through: “It was an experience for me and an honor. When my country needed me, I quit school and enlisted and served my country, and I’m proud of it.” He adds, “I’m also thankful that I’m here to talk about it.”

What great story, Sarah and I really enjoy it. We miss your home made WINE!

This was a wonderful article about Al Manfredi! My dad Chris Palomino is a good friend of Al’s and he wanted me to write this and say it is a honor to have been his friend for the past 15+ years. We just want to thank him so much for his Service and glad to call him a Friend!

Wonderfully written article. Thank you Al! What an amazing person.

Thank you Mr. Manfredi for your service. What an amazing story of your life in the Air Force. That you Pat for the article.

What a delightful article. So proud of him and so proud to say he is my uncle!