By Pat Veltri

A young man is on his knees, sobbing hysterically, screaming for his mother. The time is World War II, the place is somewhere in the Pacific on the aircraft carrier USS Essex. World War II veteran, John F. “Johnny” Bacca of Raton is telling the story. Bacca was nineteen at the time, and his young friend Norman was only seventeen. At the youthful age of sixteen, Norman lied about his age and enlisted in the Navy. In one particular instance, while their ship was preparing to do battle, and both men were heading for their battle stations, Norman lost control. “I didn’t know what to do with him,” Bacca says, “but I got down with him. He started crying and I slapped him across the face four or five time to get him out of it. He said, ‘What did you do that for?’ I said, ‘I’m scared too, but we’re alive, and until something happens, we’re still alive.’ He said, ‘How come you don’t worry about it?’ I said, ‘I think about things back home that I like, maybe some of my girl friends. I don’t think about being killed. I want you to think the same way.’ He got out of it and right after the war was over with I was the best man at his wedding. That was kind of a moment I cherish.”

While Bacca forced himself to think positively, preparing himself mentally for facing danger and possibly death, other young shipmates, like his friend Norman, probably away from home for the first time, were not as psychologically ready to deal with the hellishness of war.

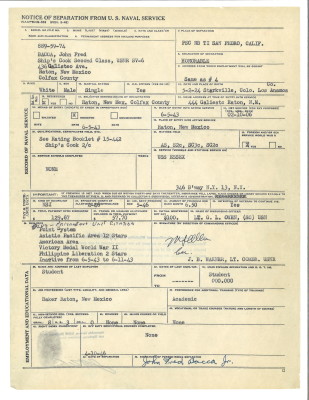

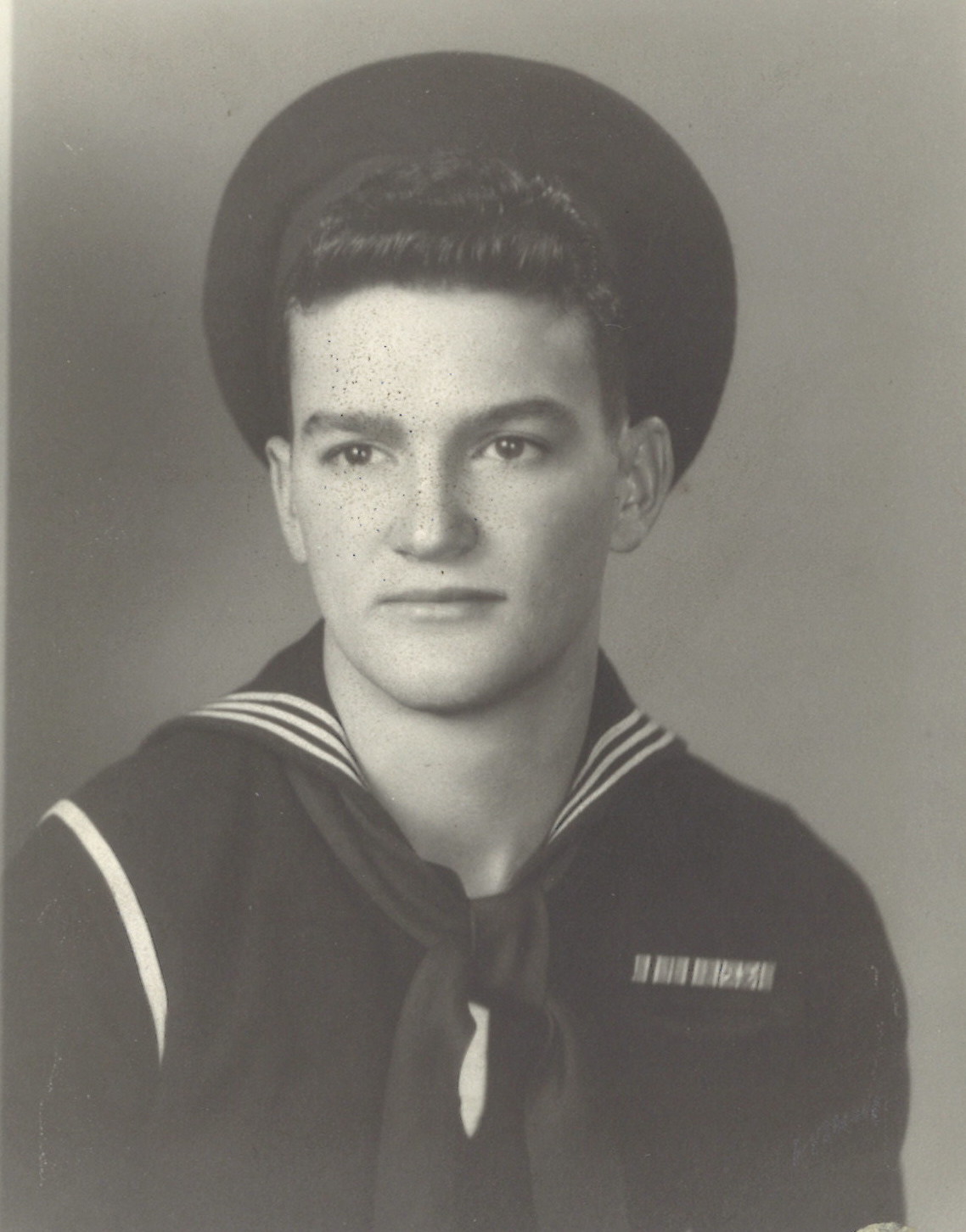

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor Bacca was more than ready to do his part for the war effort. His future wife’s brother, Billy Buhr, who was Raton’s first World War II casualty, had died at Pearl Harbor. Bacca wanted to be “in the war and in the Navy” so he volunteered for service when he was eighteen. However, he was rejected because of his eyesight. In June, 1943, he was drafted in the United States Navy. With the stipulation that he wear eyeglasses, Bacca was able to complete basic training at San Diego Naval Base. He was assigned overseas duty on the USS Essex, where he stayed for the duration of his service.

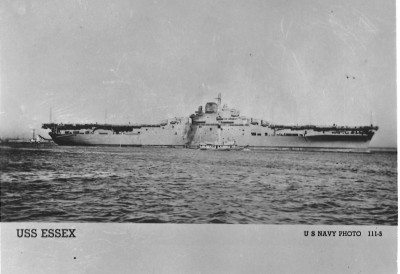

The USS Essex was built for the United States Navy by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company during World War II. The Essex was the fourth U.S. Navy ship to carry the name. Commissioned in December, 1942, it was the first of a class of aircraft carriers of which thirty-two were authorized. According to Bacca the complement (full number needed to man the ship) of the Essex was 3000, including 2400 regular Navy men and 600 pilots and officers. He recalls that the flight deck was 865 feet long, and that there were from 90 to 100 planes on the ship, including Avengers (torpedo bombers), Wildcats (fighter planes), and other dive bombers. A Marine air group with Corsair fighter aircraft was also on board. At any given time, some of the planes would be topside, gassed and ready to go, while others were housed underneath the flight deck.

Bacca’s battle station was initially in the powder room (a place where ammunition is stored), and later below the hangar deck. While the ship was under fire, he was responsible for furnishing the powder for the 85 pound projectiles fired from several five inch anti-aircraft guns. He says, “My battle station was in the powder room for a whole year and the stressful thing about that is if we were torpedoed or bombed, and there was any fire near the powder room you were automatically dead because you didn’t get out. They flooded it to save the ship.”

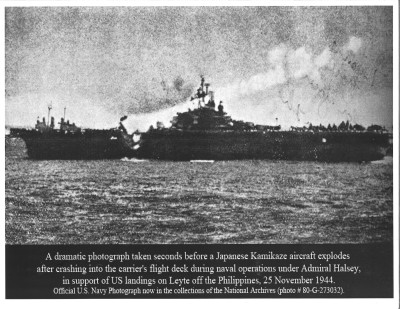

According to Bacca the Essex came under fire from Japanese air attacks about 69 times, with thirteen of those kamikaze attacks. Kamikazes were suicide attacks by young Japanese aviators, ages fifteen or younger, against allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign. They were not expert pilots, which accounted for their many misses. There was only one kamikaze hit on the Essex. On November 25, 1943, a suicide bomber hit the port edge of the Essex’s flight deck, landing among planes gassed for takeoff, causing extensive damage, and killing seventeen. Bacca remembers, “The gun mount that the kamikaze hit on the flight deck was manned at that time by Afro-Americans and they were segregated yet. One of the guys was a good friend of mine; I used to exercise with him. He saved five white guys out of the tire shop that was underneath the flight deck that was on fire. He got them out, but he died from burns three days later. He got a medal for it, posthumously.” Bacca says there was a forty foot hole in the flight deck from the hit. It was quickly patched up, and the flight deck was ready to launch a plane in 45 minutes.

According to Bacca the Essex came under fire from Japanese air attacks about 69 times, with thirteen of those kamikaze attacks. Kamikazes were suicide attacks by young Japanese aviators, ages fifteen or younger, against allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign. They were not expert pilots, which accounted for their many misses. There was only one kamikaze hit on the Essex. On November 25, 1943, a suicide bomber hit the port edge of the Essex’s flight deck, landing among planes gassed for takeoff, causing extensive damage, and killing seventeen. Bacca remembers, “The gun mount that the kamikaze hit on the flight deck was manned at that time by Afro-Americans and they were segregated yet. One of the guys was a good friend of mine; I used to exercise with him. He saved five white guys out of the tire shop that was underneath the flight deck that was on fire. He got them out, but he died from burns three days later. He got a medal for it, posthumously.” Bacca says there was a forty foot hole in the flight deck from the hit. It was quickly patched up, and the flight deck was ready to launch a plane in 45 minutes.

The Essex participated in several campaigns in the Pacific Theater of Operations, including Rabaul, Tarawa, Palau Islands, Iwo Jima, Kyushu, Okinawa, and Formosa. The ship took part in the Battle for Leyte Gulf and the offensive on Manila and the northern Philippine Islands. Bacca’s wartime medals show that he earned twelve battle stars participating in these military operations. He is especially proud of the Presidential Unit Citation that the Essex earned for all of the time it was in battle zones. At one of the ship’s last battles at Kyushu, the Essex conducted a significant search for survivors. “We saved a lot of guys that were in the water that got hit on a ship in front of us. They happened to be on the flight deck of this ship and a kamikaze hit them and they were all in the water drowning. We threw all our life preservers, our life jackets and everything we had to save them,” Bacca explains.

While there was a lull in action the ship’s crew took the opportunity to have a little fun. They played indoor games such as basketball and volleyball on the hangar deck, and there were boxing matches every Friday. Another form of entertainment was King Neptune’s Realm, an initiation rite of sorts, to commemorate a sailor’s first crossing of the equator. Bacca says, “We had one day where we celebrated crossing the equator. Everybody had a lot of fun. If you were going across for the first time you might get your hair cut off, or have to wear your clothes inside out or get whipped with a hose – something embarrassing. You weren’t actually a regular ‘salt’ (experienced sailor) until you crossed the equator. We had to go through the ceremony.”

Bacca was born in Starkville, Colorado in 1924 and moved to Raton with his parents and siblings in 1931. In 1936 Bacca’s father opened a bakery on Cook Avenue. Bacca worked in his father’s bakery from the age of twelve up until the time he was drafted into the Navy, so he was pretty good at molding bread. When he was first assigned to his ship, there was a call for volunteers in the baking or cooking departments. “I volunteered,” Bacca says “because I was a baker. I knew how to bake. I had been working with my dad all the time.” Bacca and the head baker had a “bake off”, with Bacca coming out on top. Consequently, the head baker, who was from Boston, wouldn’t accept Bacca on his crew.

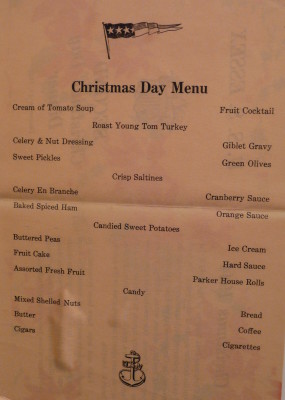

Instead Bacca became a cook striker, or apprentice, and stayed on in the galley during his three year stint in the Navy. When he mustered out of the service, he had achieved the rank of Cook Second Class, which is equivalent to the status of chef in civilian terms. “I learned a lot about quality cooking and quantity cooking; I helped to prepare 2400 meals, three times a day,” Bacca says. He worked eight to ten hour shifts, which were staggered, meaning he worked five days one week, three days the next week, etc. “If we were going into battle,” Bacca recalls, “we served an early breakfast that was something substantial; most of the time it was steak and eggs.” It took a three man crew to prepare hotcakes – 2400 sailors, three per sailor – which amounted to 7200 hotcakes!

Bacca says the meals that were served to his shipmates were tasty and nutritionally balanced, but he recalls one incident towards the end of the war, as they were preparing for the last drive for the Philippines and Formosa, when the cooking crew was forced to deal with inferior food staples for a period of several months. “Whoever bought all of our supplies bought stuff that wasn’t any good. We had to throw a lot of it away, and I don’t think that was fair for guys that were risking their lives going into battle, Bacca states.” By the time the ship reached Formosa the flour was full of weevils and the canned goods were popping open. The crew had to make do with dried food, such as beans, and whatever was in the freezer.

While Bacca feels it was a privilege to serve in World War II, he considers the experience traumatic. “I would not want to ever go through it again,” he says. “It was three years out of my life at a young age, yet it had to be done at the time.”

Bacca’s personal stance about war is that he opposes it. “I’m against any war that we’re in, unless it had to be, but as far as trying to settle something between other countries, I don’t go for that. If you’re going to go to war, go to win it, not to be just a police officer.”

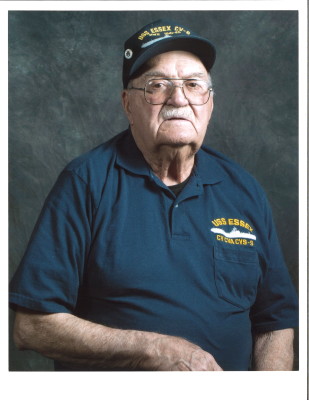

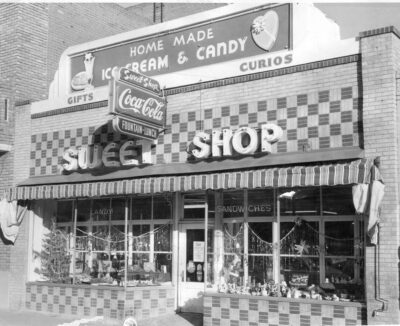

Bacca was separated from the Navy in July, 1946. In 1947 he married Mabel Buhr and opened Johnny’s Bakery. They owned and operated the bakery, a coffee shop, and a catering service for forty years, while raising a family of five children. They retired in 1987. One of Bacca’s most enjoyable retirement activities has been attending the Essex reunions that are held periodically in different locations throughout the United States. Even though he has been retired for while, Bacca continues to bake bread for his own use.

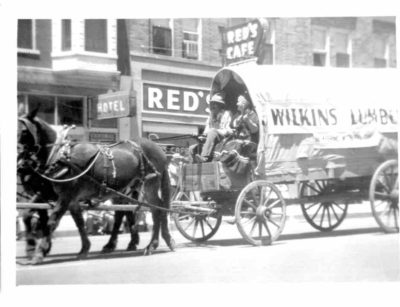

Photos, memorabilia are courtesy of Johnny Bacca.

Awesome story! Best bakery ever! What I would do for a cream puff or long john from there haha.

What a great story Johnny. And thank you for wonderful bread. My family would always talk about your long johns and everything you baked. God bless you sir!

Thank you for your service Johnny!!

He was a good friend of my dad’s…Richard Valdez. They often went fishing together. I will never forget the awesome bread, cream puffs and maple bars I bought at Johnny’s Bakery.

This story of bravery, courage and service to our country by him and countless others brought the reality of the horrors of war to a better understanding to us who never experienced anything like this. I appreciated the commradery and sense of brotherhood among the soldiers…a bond that can never be broken. May God bless each and every soldier both past and present. We owe them our respect and gratefulness for their service to us and our country.

Great story for a truly great guy.

Thank You for your service to our great nation Johnny. You are part of the Greatest Generation which is the foundation of America which generations that follow should use as an example. Your bakery was and still is an icon of Raton.

Joey Aldaz, Lt Col, USAF (Ret)